- Home

- Michael Swanwick

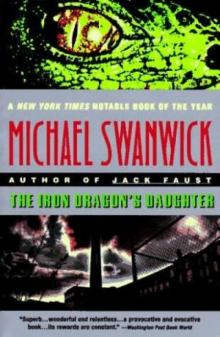

The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter Read online

The Iron Dragon's Daughter

Michael Swanwick

The changeling's decision to steal a dragon and escape was born, though she did not know it then, the night the children met to plot the death of their supervisor…

With these words, author Michael Swanwick ushers us into a remarkable realm of darkest fantasy, erotic dreams and industrial magicks—equaling the undiluted power and uniqueness of vision of his Nebula award-winning masterwork STATIONS OF THE TIDE.

Jane is a human changeling child coming of age in a world of violence and monsters. An abused outcast, she toils unceasingly alongside trolls, dwarves, shifters and feys in the dank, stygian bowels of a steam dragon plant—helping to construct the massive, black iron flying machines the elvan rulers use for waging war. Young Jane's days are bleak and her future seems hopeless—until a cold yet tantalizing inner voice whispers to her of high lakes, autumn stars…and freedom.

The voice leads her to a junkyard dragon—old and broken, kept alive by hatred and a still-unsatisfied thirst for blood. And he promises to help Jane escape, if she will, in turn, help him to fly again. But untold wonders and terrors both lie beyond the factory gates—where a true name is a weapon…and erotic temptations wait to corrupt a young girl already hardened by life's cruel inequities.

A quick mind and a taste and talent for thievery will sustain Jane, however, on her strange and arduous journey from slave to student, from alchemist to avenger—while drugs and dreams transport her Elsewhere, on fleeting trips to a stolen reality. And through it all, the dragon lurks in the shadows—filling her head with violent visions, drawing her into a web of unknown plots and unseen forces. And, ultimately, at his controls, the changeling will confront the powers that have always ruled her life—seeking impossible answers through the obliteration of history…and the end of all things.

World Fantasy (nominee)

Arthur C. Clarke Award (nominee)

The Iron Dragon's Daughter

MICHAEL SWANWICK

FOR TESS KISSINGER AND BOB WALTERS

who didn't suspect I was stealing part of their story

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Greg Frost for his encouragement and suggestions and for spotting the significance of the shadow-boy, Bob and Tess for dirt on insurgencies and rich relations, Susan Duggan for help navigating Penn, Dr. David Van Dyke for the p-chem here misapplied and for electric pickles as well, Gardner and Susan for football yobboes, Janet Kagan for help with French neologisms, Dafydd ab Hugh for Celtic words left on the cutting room floor, Gail Roberts for Dickens references, Elizabeth Willey for funding the University's carillon and one of its bathrooms, Lucia St. Clair Robson for the Gordon Riots and the Half-Crown Chuck Office, and Sean for his many insights. Health insurance and emotional support were provided by the M.C. Porter Endowment for the Arts.

— 1 —

THE CHANGELING'S DECISION TO STEAL A DRAGON AND ESCAPE was born, though she did not know it then, the night the children met to plot the death of their supervisor.

She had lived in the steam dragon plant for as long as she could remember. Each dawn she was marched with the other indentured minors from their dormitory in Building 5 to the cafeteria for a breakfast she barely had time to choke down before work. Usually she was then sent to the cylinder machine shop for polishing labor, but other times she was assigned to Building 12, where the black iron bodies were inspected and oiled before being sent to the erection shop for final assembly. The abdominal tunnels were too small for an adult. It was her duty to crawl within them to swab out and then grease those dark passages. She worked until sunset and sometimes later if there was a particularly important dragon under contract.

Her name was Jane.

The worst assignments were in the foundries, which were hellish in summer even before the molds were poured and waves of heat slammed from the cupolas like a fist, and miserable in winter, when snow blew through the broken windows and a gray slush covered the work floor. The knockers and hogmen who labored there were swart, hairy creatures who never spoke, blackened and muscular things with evil red eyes and intelligences charred down to their irreducible cinders by decades-long exposure to magickal fires and cold iron. Jane feared them even more than she feared the molten metals they poured and the brute machines they operated.

She'd returned from the orange foundry one twilit evening too sick to eat, wrapped her thin blanket tight about her, and fallen immediately asleep. Her dreams were all in a jumble. In them she was polishing, polishing, while walls slammed down and floors shot up like the pistons of a gigantic engine. She fled from them under her dormitory bed, crawling into the secret place behind the wallboards where she had, when younger, hidden from Rooster's petty cruelties. But at the thought of him, Rooster was there, laughing meanly and waving a three-legged toad in her face. He chased her through underground caverns, among the stars, through boiler rooms and machine shops.

The images stabilized. She was running and skipping through a world of green lawns and enormous spaces, a strangely familiar place she knew must be Home. This was a dream she had often. In it, there were people who cared for her and gave her all the food she wanted. Her clothes were clean and new, and nobody expected her to put in twelve hours daily at the workbench. She owned toys.

But then as it always did, the dream darkened. She was skipping rope at the center of a vast expanse of grass when some inner sense alerted her to an intrusive presence. Bland white houses surrounded her, and yet the conviction that some malevolent intelligence was studying her increased. There were evil forces hiding beneath the sod, clustered behind every tree, crouching under the rocks. She let the rope fall to her feet, looked about wonderingly, and cried a name she could not remember.

The sky ripped apart.

"Wake up, you slattern!" Rooster hissed urgently. "We coven tonight. We've got to decide what to do about Stilt."

Jane jolted awake, heart racing. In the confusion of first waking, she felt glad to have escaped her dream, and sorry to have lost it. Rooster's eyes were two cold gleams of moonlight afloat in the night. He knelt on her bed, bony knees pressing against her. His breath smelled of elm bark and leaf mold intermingled. "Would you mind moving? You're poking into my ribs."

Rooster grinned and pinched her arm.

She shoved him away. Still, she was glad to see him. They'd established a prickly sort of friendship, and Jane had come to understand that beneath the swagger and thoughtlessness, Rooster was actually quite nice. "What do we have to decide about Stilt?"

"That's what we're going to talk about, stupid!"

"I'm tired," Jane grumbled. "I put in a long day, and I'm in no mood for your hijinks. If you won't tell me, I'm going back to sleep."

His face whitened and he balled his fist. "What is this—mutiny? I'm the leader here. You'll do what I say, when I say, because I say it. Got that?"

Jane and Rooster matched stares for an instant. He was a mongrel fey, the sort of creature who a century ago would have lived wild in the woods, emerging occasionally to tip over a milkmaid's stool or loosen the stitching on bags of milled flour so they'd burst open when flung over a shoulder. His kind were shallow, perhaps, but quick to malice and tough as rats. He worked as a scrap iron boy, and nobody doubted he would survive his indenture.

At last Jane ducked her head. It wasn't worth it to defy him.

When she looked up, he was gone to rouse the others. Clutching the blanket about her like a cloak, Jane followed. There was a quiet scuffling of feet and paws, and quick exhalations of breath as the children gathered in the center of the room.

Dimity produced a stolen candle stub and wedged it in the widest part of a crack between two

warped floorboards. They all knelt about it in a circle. Rooster muttered a word beneath his breath and a spark leaped from his fingertip to the wick.

A flame danced atop the candle. It drew all eyes inward and cast leaping phantasms on the walls, like some two-dimensioned Walpurgisnacht. Twenty-three lesser flames danced in their irises. That was all dozen of them, assuming that the shadow-boy lurked somewhere nearby, sliding away from most of the light and absorbing the rest so thoroughly that not a single photon escaped to betray his location.

In a solemn, self-important voice, Rooster said: "Blugg must die." He drew a gooly-doll from his jerkin. It was a misshapen little thing, clumsily sewn, with two large buttons for eyes and a straight gash of charcoal for a mouth. But there was the stench of power to it, and at its sight several of the younger children closed their eyes in sympathetic hatred. "Skizzlecraw has the crone's-blood. She made this." Beside him, Skizzlecraw nodded unhappily. The gooly-doll had been her closely guarded treasure, and the Lady only knew how Rooster had talked her out of it. He brandished it over the candle. "We've said the prayers and spilt the blood. All we need do now is sew some touch of Blugg inside the stomach and throw it into a furnace."

"That's murder!" Jane said, shocked.

Thistle snickered.

"I mean it! And not only is it wrong, but it's a stupid idea as well." Thistle was a shifter, as was Stilt himself, and like all shifters she was something of a lack-wit. Jane had learned long ago that the only way to silence Thistle was to challenge her directly. "What good would it do? Even if it worked—which I doubt—there'd be an investigation afterwards. And if by some miracle we weren't discovered, they'd still only replace Blugg with somebody every bit as bad. So what's the point of killing him?"

That should have silenced them. But to Jane's surprise, a chorus of angry whispers rose up like cricket song.

"He works us too hard!"

"He beats me!"

"I hate that rotten Old Stinky!"

"Kill him," the shadow-boy said in a trembling voice from directly behind her left shoulder. "Kill the big dumb fuck!" She whirled about and he wasn't there.

"Be still!" Casting a scornful look at Jane, Rooster said, "We have to kill Blugg. There is no alternative. Come forward, Stilt."

Stilt scooched a little closer. His legs were so long that when he sat down his knees were higher than his head. He slipped a foot out of his buskin and unselfconsciously scratched himself behind an ear.

"Bend your neck."

The scrawny young shifter obeyed. Rooster shoved the head farther down with one hand, and with the other pushed aside the lank, ditchwater hair. "Look—pin-feathers!" He yanked up Stilt's head again, and waggled the sharp, foot-long nose to show how it had calcified. "And his toes are turning to talons—see for yourselves."

The children pushed and shoved at one another in their anxiety to see. Stilt blinked, but suffered their pokes and prods with dim stoicism. Finally, Dimity sniffed and said, "So what?"

"He's coming of age, that's so what. Look at his nose! His eyes! Before the next Maiden's Moon, the change will be upon him. And then, and then…" Rooster paused dramatically.

"Then?" the shadow-boy prompted in a papery, night-breeze of a voice. He was somewhere behind Thistle now.

"Then he'll be able to fly!" Rooster said triumphantly. "He'll be able to fly over the walls to freedom, and never come back."

Freedom! Jane thought. She rocked back on her heels, and imagined Stilt flapping off clumsily into a bronze-green autumn sky. Her thoughts soared with him, over the walls and razor wire and into the air, the factory buildings and marshaling yards dwindling below, as he flew higher than the billowing exhaust from the smokestacks, into the deepening sky, higher than Dame Moon herself. And never, oh never, to return!

It was impossible, of course. Only the dragons and their half-human engineers ever left the plant by air. All others, workers and management alike, were held in by the walls and, at the gates, by security guards and the hulking cast-iron Time Clock. And yet at that instant she felt something take hold within her, a kind of impossible hunger. She knew now that the idea, if nothing more, of freedom was possible, and that established, the desire to be free herself was impossible to deny.

Down at the base of her hindbrain, something stirred and looked about with dark interest. She experienced a moment's dizzy nausea, a removal into some lightless claustrophobic realm, and then she was once again deep in the maw of the steam dragon plant, in the little dormitory room on the second floor of Building 5, wedged between a pattern storeroom and the sand shed, with dusty wooden beams and a tar paper roof between her and the sky.

"So he'll get to fly away," Dimity said sourly. Her tail lashed back and forth discontentedly. "So what? Are we supposed to kill Blugg as a going-away present?"

Rooster punched her on the shoulder for insubordination. "Dolt! Pimple! Douchebag! You think Blugg hasn't noticed? You think he isn't planning to make an offering to the Goddess, so she'll keep the change away?"

Nobody else said anything, so reluctantly Jane asked, "What kind of offering?"

He grabbed his crotch with one hand, formed a sickle with the other, and then made a slicing gesture with the sickle. His hand fell away. He raised an eyebrow. "Get it?"

She didn't really, but Jane knew better than to admit that. Blushing, she said, "Oh."

"Okay, now, I've been studying Blugg. On black foundry days, he goes to his office at noon, where he can watch us through the window in his door, and cuts his big, ugly nails. He uses this humongous great knife, and cuts them down into an ashtray. When he's done, he balls them up in a paper napkin and tosses it into the foundry fires, so they can't be used against him.

"Next time, though, I'm going to create a disturbance. Then Jane will slip into his office and steal one or two parings. No more," he said, looking sternly at her, "or he'll notice."

"Me?" Jane squeaked. "Why me?"

"Don't be thick. He's got his door protected from the likes of the rest of us. But you—you're of the other blood. His wards and hexes won't stop you"

"Well, thanks heaps," Jane said. "But I won't do it. It's wrong, and I've already told you why." Some of the smaller children moved toward her threateningly. She folded her arms. "I don't care what you guys say or do, you can't make me. Find somebody else to do your dirty work!"

"Aw, c'mon. Think of how grateful we'd all be." Rooster got up on one knee, laid a hand across his heart, and reached out yearningly. He waggled his eyebrows comically. "I'll be your swain forever."

"No!"

Stilt was having trouble following what they were saying. In his kind this was an early sign of impending maturity. Brow furrowed, he turned to Rooster and haltingly said, "I… can't fly?"

Rooster turned his head to the side and spat on the floor in disgust. "Not unless Jane changes her mind."

Stilt began to cry.

His sobs began almost silently, but quickly grew louder. He threw back his head, and howled in misery. Horrified, the children tumbled over one another to reach him and stifle his cries with their hands and bodies. His tears muffled, then ceased.

For a long, breathless moment they waited to hear if Blugg had been roused. They listened for his heavy tread coming up the stairs, the angry creaking of old wood, felt for the stale aura of violence and barely suppressed anger that he pushed before him. Even Rooster look frightened.

But there came no sound other than the snort of cyborg hounds on patrol, the clang and rustle of dragons in the yards stirring restlessly in their chains, and the distant subaudible chime of midnight bells celebrating some faraway sylvan revelry. Blugg still slept.

They relaxed.

What a shivering, starveling batch they were! Jane felt a pity for them all that did not exclude herself. A kind of strength hardly distinguishable from desperation entered her then and filled her with resolve, as though she were nothing more than an empty mold whose limbs and torso had been suddenly poured through with molten ir

on. She burned with purpose. In that instant she realized that if she were ever to be free, she must be tough and ruthless. Her childish weaknesses would have to be left behind. Inwardly she swore, on her very soul, that she would do whatever it took, anything, however frightening, however vile, however wrong.

"All right," she said. "I'll do it."

"Good." Without so much as a nod of thanks, Rooster began elaborating his plot, assigning every child a part to play. When he was done, he muttered a word and made a short, chopping pass with his hand over the candle. The flame guttered out.

Any one of them could've extinguished it with the slightest puff of breath. But that wouldn't have been as satisfying.

* * *

The black foundry was the second largest work space in all the plant. Here the iron was poured to make the invulnerable bodies and lesser magick-proofed parts of the great dragons. Concrete pits held the green sand, silt mixes, and loam molds. Cranes moved slowly on overhead beams, and the October sunlight slanted down through airborne dust laboriously churned by gigantic ventilating fans.

At noon an old lake hag came by with the lunch cart, and Jane received a plastic-wrapped sandwich and a cup of lukewarm grapefruit juice for her portion. She left her chamois gloves at the workbench, and carried her food to a warm, dusty niche beside a wood frame bin filled with iron scrap, a jumble of claws, scales, and cogwheels.

Jane set the paper cup by her side, and smoothed her coarse brown skirt comfortably over her knees. Closing her eyes, she pretended she was in a high-elven cloud palace. The lords and ladies sat about a long table, all marble and white lace, presided over by slim tapers in silver sticks. The ladies had names like Fata Elspeth and Fata Morgaine, and spoke in mellifluous polysyllables. Their laughter was like little bells and they called her Fata Jayne. An elven prince urged a bowl of sorbet dainties on her. There was romance in his eyes. Dwarven slaves heaped the floor with cut flowers in place of rushes.

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors