- Home

- Michael Swanwick

Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Read online

Dancing with Bears

Michael Swanwick

Dancing with Bears

Michael Swanwick

SOMETIME EARLIER…

T he last man was led stumbling to the edge of the city. Long ago, Baikonur had been a bright jewel of human aspiration, a place from which ancient heroes rode tremendous machines beyon d the sky. Now it was a colony of Hell. The sun had set and the city was shrouded in smoke. But the red glow of furnaces and sudden gouts of gas flares lit up disconnected fragments of the incomprehensible structures that wound themselves about the ruins from the Age of Space. They revealed an ugliness that only a fiend could love.

The man was naked. To either side of him, all but invisible in the starless night, walked or loped metal demons, sometimes on two legs and sometimes on four. If he lagged, they drove him along with shoves on his shoulders and sharp nips at his heels. Through a forest of metal they traveled, under tangles of pipes, and past autonomous machines that were angrily hammering, ripping, welding, digging. The noise was painful to the man, but by this point, pain hardly mattered anymore.

At the edge of the city, they stopped. “Look up, human,” said one of the demons.

Reluctantly, he obeyed.

The division between the city and the wild was absolute. In the length of a single step, soaring grotesqueries of iron and cement gave way to scrub vegetation. The air was still foul with smoke. But beneath the stench of coal fires and chemicals was a hint of the spicy smell of the desert. Far ahead, an intensification of the darkness marked the low hills beyond Baikonur.

The man took a deep breath and coughed, almost choking. Then he said, “I am glad to see this before I die.” “Perhaps you won’t die.”

To either side of him, the man saw shadows slipping out of the city and coming to a crouch at its fringe. He recognized them as the same kind of machines as those which had captured him, imprisoned him, tortured him, and just now brought him here. “Whatever your game is, I won’t play it.”

“We have perfected the drug distilled from your misery and a reliable courier carries it to Moscow to be replicated,” the demon said. “Your usefulness has therefore come to an end. So we will give you a head start-all the way to the hills-before we come after you.”

“This is what happened to my comrades, isn’t it? You brought them here, one by one, released them, and hunted them down.”

“Yes.”

“Well, I have suffered too much already. I won’t let you play with me any more-and nothing you can say will make me change my mind.”

The demons neither moved nor spoke for a long time. Irrational though the thought was, the man wondered if they were communicating with one another silently. At last, a second demon spoke from the darkness. “One of your kind escaped us once, years ago. Perhaps you will be the second.”

Uncertainly, the last man in Baikonur turned his face to the north. He began to walk. And then to run.

…1…

Deep in the heart of the Kremlin, the Duke of Muscovy dreamt of empire. Advisors and spies from every quarter of the shattered remnants of Old Russia came to whisper in his ear. Most he listened to impassively. But sometimes he would nod and mumble a few soft words. Then messengers would be sent flying to provision his navy, redeploy his armies, comfort his allies, humor those who thought they could deceive and mislead him. Other times he sent for the head of his secret police and with a few oblique but impossible to misunderstand sentences, launched a saboteur at an enemy’s industries or an assassin at an insufficiently stalwart friend.

The great man’s mind never rested. In the liberal state of Greater St. Petersburg, he considered student radicals who dabbled in forbidden electronic wizardry, and in the Siberian polity of Yekaterinburg, he brooded over the forges where mighty cannons were being cast and fools blinded by greed strove to recover lost industrial processes. In Kiev and Novo Ruthenia and the principality of Suzdal, which were vassal states in all but name, he looked for ambitious men to encourage and suborn. In the low dives of Moscow itself, he tracked the shifting movements of monks, gangsters, dissidents, and prostitutes, and pondered the fluctuations in the prices of hashish and opium. Patient as a spider, he spun his webs. Passionless as a gargoyle, he did what needed to be done. His thoughts ranged from the merchant ports of the Baltic Sea to the pirate shipyards of the Pacific coast, from the shaman-haunted fringes of the Arctic to the radioactive wastes of the Mongolian Desert. Always he watched.

But nobody’s thoughts can be everywhere. And so the mighty duke missed the single greatest threat to his ambitions as it slipped quietly across the border into his someday empire from the desolate territory which had once been known as Kazakhstan…

The wagon train moved slowly across the bleak and empty land, three brightly painted and heavily laden caravans pulled by teams of six Neanderthals apiece. The beast-men plodded stoically onward, glancing neither right nor left. They were brutish creatures whose shaggy fleece coats and heavy boots only made them look all the more like animals. Bringing up the rear was a proud giant of a man on a great white stallion. In the lead were two lesser figures on nondescript horses. The first was himself nondescript to the point of being instantly forgettable. The second, though possessed of the stance and posture of a man, had the fur, head, ears, tail, and other features of a dog.

“Russia at last!” Darger exclaimed. “To be perfectly honest, there were times I thought we would never make it.”

“It has been an eventful journey,” Surplus agreed, “and a tragic one as well, for most of our companions. Yet I feel certain that now we are so close to our destination, adventure will recede into memory and our lives will resume their customary placid contours once more.”

“I am not the optimist you are, my friend. We started out with forty wagons and a company of hundreds that included scholars, jugglers, gene manipulators, musicians, storytellers, and three of the best chefs in Byzantium. And now look at us,” Darger said darkly. “This has been an ill-starred expedition, and it can only get worse.”

“Yet we survive, and the ambassador and the Caliph’s treasures as well. Surely this is an omen that, however badly she may deal with others, Dame Fortune is unreservedly on our side.”

“Perhaps,” Darger said dubiously. He scowled down at the map unfolded across his saddle. “According to this, we should have reached Gorodishko long ago. Yet somehow it continues to recede from us as steadily and maddeningly as do our dreams of wealth.” He folded the map and put it away in a flapped pocket that a now-dead leather worker had sewn for that express purpose onto his klashny’s scabbard. “If fortune smiles on us, then let her give us a sign.”

Just then, a horse, reins loose and saddle empty, topped a rise in the road ahead and came trotting toward them.

Darger blinked in astonishment. But his comrade, ever quick to action, wheeled about his mount and, as the horse passed them, seized the reins and brought the animal to a halt. Surplus had already dismounted and was calming the runaway when the ambassador rode up, mustaches a-bristle with indignation.

“Sons of indolence and misfortune! What treachery do you plot now?”

Darger, who had long ago grown used to his employer’s extravagant rhetoric, took this as a simple inquiry. “This horse appears to have thrown its rider, Prince Achmed.”

“It is lathered from running,” Surplus added. “We should pause to wipe it down. Then we should set about finding its fallen rider. He may be in distress.”

“The rider must see to himself,” Prince Achmed said. “My mission is too important for us to go haring off into the countryside looking for some careless lout who doubtless was inspired to fall from his mount by an excess of alcohol. The horse is salvage and I shall add it to

our woefully depleted resources.”

“At least,” Darger said, “let us remove the poor creature’s saddle and saddlebags.”

“So that you and your dog-faced crony can plunder their contents? Allah forbid that I should ever grow so weak-minded as to permit that!”

Drawing himself up to his tallest, Darger said coldly, “No man can with justice accuse me of being a thief.”

“Can he not? Can he not?” Prince Achmed’s lips tightened. Then, with sudden resolution, he wheeled his horse about, galloped back to the last wagon, and rapped briskly at the door. A slide-hole opened briefly, he spoke a few words, and it shut again.

“This does not look good,” Darger murmured. “Do you suppose he has found the letter?”

Surplus shrugged.

The door opened for an instant and when it slammed shut, the ambassador held a dispatch case with a long leather strap. He cantered back to the pair.

“Do you see this?” He shook the case in their faces. “Does it perhaps look familiar to you?”

“Really, sir.” Darger sighed. “Need we bandy rhetorical questions at one another?”

“We saw it first from our ship,” Surplus said. “Midway up the Caspian, on a drear and rocky shore, the lookout espied a crudely made hut such as a castaway might build, with three poles erected before it. On one was the flag of the Byzantine Empire. The second flew a courier’s ensign. On the third was a black biohazard pennant. In the doorway of the hut hung this case. Together these four items told us that a messenger had been sent at some time after our departure from Byzantium, that he had taken the direct route through the plague-lands of the Balkans, and that in doing so, the poor fellow had paid for his courage by contracting one of the many war viruses yet endemic to that unhappy region.”

“You took a boat ashore and retrieved the case. Alone.”

“To be fair, sir, that was done at your command.”

“You thought that Surplus, being genetically modified into human form and feature and yet still possessed of the genome of the noble dog, would most likely be immune from any disease the courier might have,” Darger amplified. “He and I argued against your reasoning-vigorously, I might add-but we were overruled. You threatened to split open both our heads and, if I recall your exact words, ‘feed their worthless contents to the crabs.’”

“In any case, I went,” Surplus resumed. “A glance within the hut sufficed to establish that the messenger was dead. I retrieved his case as required and presented it to you. And now, here it is.”

The prince smiled sourly. “I thought it odd at the time that the case contained nothing of any serious moment. All the letters were transient and inconsequential, the sorts of things that would be included so long as a courier was already going to Moscow anyway. But there was nothing that in and of itself would prompt so hazardous a journey. I watched you carefully from the ship, and though you did indeed rummage through the bag-”

“I was merely determining that its contents were undamaged.”

“-you had no opportunity to discard a letter. The strand was empty and you were being observed every minute. Many times over the too-eventful weeks since, I have mused on this paradox. Until finally the answer came to me.” The prince reached inside the case. “The bottom, you will note, is reinforced with a second layer of leather. The stitching has come undone along one side. It would be the easiest thing in the world for a scoundrel to slide an envelope beneath, where it would easily escape detection.”

With a flourish, Prince Achmed produced a letter in the distinctive red envelope-and-seal of the Byzantine Secret Service. “Behold! A careful accounting of your perfidy and deceit. Which you tried to conceal from me.”

Surplus raised his snout disdainfully. “I never saw the thing before this moment. It must have been placed where you found it by the messenger, for motives known only to himself.”

The ambassador flung away the case and shook the letter open with his left hand. “To begin: You obtained your current situations as my secretaries by presenting me with forged letters of commendation from the Sultan of Krakow-a personage and indeed a position which, under later investigation, turned out not to exist.”

“Sir, everybody puffs their resume. ’Tis a venial sin, at worst.”

“You said you were personal favorites of the Council of Magi and thus able to secure passage through Persia without bribery. Later, when this turned out not to be true, you claimed there had been a change in leadership and your patrons were out of political favor. The truth, it turns out, is that erenow you had never been east of Byzantium.”

“A little white lie,” Darger said urbanely. “We have business in Moscow and you were heading in that direction. It was the only way we could join your caravan. True, the Council of Magi did require you to pay them handsomely. But they would have done so in any case. So our deceit cost you nothing.”

The ambassador’s right hand whitened on the hilt of his scimitar. His horse, sensing his tension, pawed the ground uneasily. “Further, it says here, you are both notorious confidence-men and swindlers who have defrauded your way through the entirety of Europe.”

“Swindlers is such a harsh word. Say rather that we live by our wits.”

“In any case,” Surplus said, “save for the Neanderthals, we are all the staff you have left. And the Neander-men, strong though they are and loyal though they have no choice but to be, are hardly to be relied upon in an emergency.”

The lead Neanderthal, one Enkidu by name, turned and curled his lip. “Fuck you, Bub.”

“I meant no insult,” Surplus said. “Only that there may be situations where quick wits count for more than strength.”

“Fuck yer mama, too.”

Ignoring him, the ambassador said, “In Paris, you sold a businessman the location of the long-lost remains of the Eiffel Tower. In Stockholm, you dispensed government offices and royal titles to which you had no claim. In Prague, you unleashed a plague of golems upon an unsuspecting city.”

“The golem is a supernatural creature, and thus nonexistent,” Darger stipulated. His mount whickered, as if in agreement. “Those you speak of were either robots or androids-the taxonomy gets a bit muddled, I admit-and in either instance, revenant technology from the Utopian era. We did Prague a favor by discovering their existence before they had the chance to do any real damage.”

“You burned London to the ground!”

“We were there when it burned, granted. But it was hardly our fault. Not entirely. Anyway, I understand that large swaths of it survived.”

“All this is ancient history,” Surplus said firmly. “The important thing to keep in mind is your mission. The Pearls Beyond Price which the Caliph himself entrusted you to bestow upon his cousin, the Duke of Muscovy, in token of their mutual, abiding, and brotherly love and with the hope that this might predispose the duke to agree to certain trade arrangements when passage between the nations is normalized. Sir, an ambassador with only two secretaries is the victim of tragic circumstances. An ambassador with none is merely laughable.”

“Yes…yes. It is all that keeps you alive,” Prince Achmed growled. Then, mastering his anger, “This conversation grows tedious. Your loyalty is dubious at best, and I shall have to give your ultimate fate long and serious thought when we reach Moscow. However, at the moment I am, as you point out, short of servitors and you still serve some functions, though not many. Navigation for one. I trust you will find this… Gogorodski… soon?”

“Gorodishko,” Darger said. He got out the map and pointed. “It is just a little further down the road.”

“You do know how to read a map, I hope?” the prince said sneeringly. Without waiting for a reply, he rode off. The riderless horse he took with him, to tether to the rear caravan so it might walk off its sweat.

Darger took out the map again and glowered down at it. “I did until today.”

But though day turned to dusk and the air grew chill, Gorodishko failed to appear.

&nb

sp; Darger had resigned himself to admitting failure and was casting about for a likely spot to pitch camp when he saw, far ahead, a spark of light by the ruins of an ancient church. As they approached, the light grew and resolved into a campfire built on a patch of bare earth between church and road. A hooded figure sat hunched by the fire. He did not stand at the caravan’s approach.

“Ho! Friend!” Darger cried. When the man did not respond, Darger galloped ahead of the rest of the party. At the fire, he dismounted and approached with his arms held up and away from his sides, to show his peaceful intent. “We are looking for a place called Gorodishko. Perhaps you can help us?”

The man’s head bobbed, as if he were chewing away at something with all his might. Still, he did not speak.

“Good sir,” Darger said, enunciating his words clearly and slowly in the hope that this fellow, doubtless a foreigner, had some fluency in English. “We are in need of a tavern of the better sort or, failing that, a-”

The man shook himself furiously and his cloak flew open to reveal ropes binding his arms to his sides and both legs together. All this Darger saw in a flash. In that same instant he saw too that the man had been tied to a post to keep him sitting upright, and that stakes had been pounded into the earth to anchor further ropes holding him immobile.

He had been staked out like a goat in a tiger hunt.

Spitting out the remnants of a shredded gag, the man cried, “Kybervolk!”

Something gray and furry and with metal teeth flashed from the shadows of the church. It leapt straight at Darger’s chest. In astonished panic, Darger tried to turn and run, but managed only to trip over his own feet. He fell flat on his back.

Which was the saving of him.

The wolfish form passed harmlessly over Darger’s body. Simultaneously, he heard three hard flat cracks as Surplus fired his klashny. Gouts of dark fluid spurted from the thing’s body. It should have died then and there. Yet it landed solidly on all four paws and immediately ran, snarling, at Surplus’s horse, which had panicked and which he was trying to bring under control again.

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

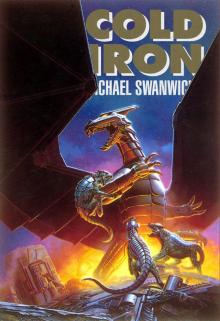

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

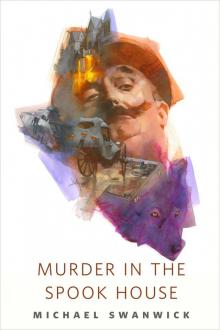

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

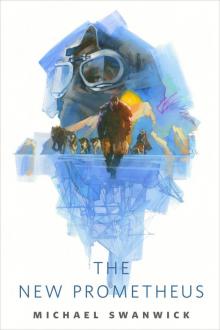

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

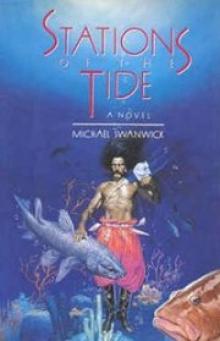

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors