- Home

- Michael Swanwick

Dancing with Bears Page 2

Dancing with Bears Read online

Page 2

By now Prince Achmed-who, whatever his faults, did not lack courage-had drawn his scimitar and driven his horse forward, shielding Surplus from his attacker.

The monster leapt.

Bodies tangled, wolf and ambassador fell from the rearing stallion.

Then a huge hand reached into the snarl of flesh and effortlessly pulled the wolf free. It whipped its head around, jaws snapping furiously and sparks flying from its mouth. But Enkidu, the largest and brawniest of the Neanderthals, was undaunted. He grasped the wolf by throat and head. Then he hoisted the ravening creature into the air and with a sudden twisting motion, broke its neck.

Enkidu flung the body to the ground. Its head lolled lifelessly. Nevertheless, its feet still scrabbled at the earth, seeking purchase. Weakly, it managed to stand. But then the second and third Neanderthals, Goliath and Herakles, arrived and stomped down hard on its spine with their boots. Five, six, seven times their feet came down, and at last it went motionless.

In death, the creature was revealed as some ungodly amalgam of wolf and machine. Its teeth and claws were sharpened steel. Where a patch of its fur had been torn away, tiny lights faded and died.

“Quick wits, eh?” Enkidu said scornfully. “Asshole.” He and his comrades turned as one and lumbered away, back to the caravans, where the bulk of their brothers stood guard over the priceless treasures within.

The entire battle, from start to finish, had taken less than a minute.

Surplus dismounted and saw to Prince Achmed, while Darger untied the stranger. The ropes fell away, and the man woozily rose to his feet. His clothes were Russian, and his face could belong to no other people. “Are you all right, sir?” Darger asked.

The Russian, a burly man with a great black beard, embraced him fervently. “Spasibo! Ty spas moyu zhizn’. Eto chudovische moglo ubit’ menya.” He kissed Darger on both cheeks.

“Well, he certainly seems grateful enough,” Darger commented wryly.

Surplus looked up from the prone body. “Darger, the ambassador is not well.”

A quick examination of the fallen man revealed no broken bones, nor any serious injuries, save four long scratches that the claws of one of the machine-wolf’s paws had opened across his face. Yet he was not only unconscious but pale to the point of morbidity. “What’s that smell?” Surplus leaned over the ambassador’s face and inhaled deeply. Then he went to the fallen wolf and sniffed at its claws. “Poison!”

“Are you certain?”

“There can be no doubt.” Surplus wrinkled his nose with distaste. “Just as there can be no doubt that this wolf was already dead when it attacked us, and had been for some time. Its body has begun to rot.”

Darger considered himself a man of science. Nevertheless, a thrill of superstitious dread ran up his spine. “How can that be?”

“I do not know.” Surplus held up the wolf ’s paw-strangely articulated metal scythes extended from its toe-pads-and then let it drop. “Let us see to our employer.”

Under Surplus’s supervision, two of the Neanderthals produced a litter from the mound of luggage lashed to a caravan roof and laid the prince’s unconscious body gently down on it. They carefully donned silk gloves, then, and carried the litter to the rear car. Surplus knocked deferentially. A peephole slid open in the door. “We need your medical expertise.” Surplus gestured. “The prince…I fear he is poisoned.” The peephole snapped shut. Then, after Surplus had withdrawn, the door swung open, and the Neanderthals slid the body into the darkness within. They backed down the steps and bowed again.

The door slammed shut.

The Neanderthals ungloved themselves and resumed their positions in the traces. Enkidu grunted a command and, with a jerk, the caravans started forward again.

“Do you think he will live?” Darger anxiously asked Surplus.

Herakles glanced sideways. “He will if he don’t die.” Then, as a harness-mate punched him appreciatively in the shoulder: “Haw!” He shoved the Neanderthal in front of him to get his attention. “Did ya hear that? He asked if Prince Ache-me was gonna live and I said-”

The Russian they had rescued, meanwhile, had found his horse and untied it from the rear of the last caravan. He had been listening to all that was said, though with no obvious comprehension. Now he spoke again. “Ty ne mozhesh’ ponyat’, chto ya skazal?”

Darger spread his hands helplessly. “I’m afraid I don’t speak your language.”

“Poshla!” the Russian said, and the horse knelt before him. He rummaged within a saddlebag and emerged with a hand-tooled silver flask. “Vypei eto, I ty poimesh’!” He held up the flask and mimed drinking from it. Then handed it to Darger.

Darger stared down at the flask.

Impatiently, the Russian snatched it back, unscrewed the top, and took a long pull. Then, with genuine force, he thrust the flask forward again.

To have done anything but to drink would have been rude. So Darger drank.

The taste was familiar, dark and nutty with bitter, yeasty undertones. It was some variety of tutorial ale, such as was commonly used in all sufficiently advanced nations to convey epic poetry and various manual skills from generation to generation.

For a long moment, Darger felt nothing. He was about to say as much when he experienced a sharp twinge and an inward shudder, such as invariably accompanied a host of nanoprogrammers slipping through the blood-brain barrier. In less time than it took to register the fact, he felt the Russian language assemble itself within his mind. He swayed and almost fell.

Darger moved his jaw and lips, letting the language slush around in his mouth, as if he were tasting a new and surprising food. Russian felt different from any other language he’d ever ingested, slippery with sha’s and shcha’s and guttural kha’s, and liquid with palatalized consonants of all sorts. It affected the way he thought as well. Its grammatical structure was very much concerned with how one went somewhere, exactly where one was going when one went, and whether or not one expected to come back. It specified whether one was going by foot or by conveyance, and there were verb prefixes to stipulate whether one was going up to something or through it or by it or around it. It distinguished between acts done habitually (going to the pub of an evening, say) or just the once (going to that same pub for a particular purpose). Which clarity might well prove useful to a man in Darger’s line of business, when making plans. At the same time, the language viewed many situations impersonally-it is necessary, it is possible, it is impossible, it is forbidden. Which might also prove useful to a man in his line of business, particularly when dealing with matters of conscience.

Still feeling a trifle giddy, Darger exhaled a short, explosive gasp of breath. “Thank you,” he said in Russian, as he passed the flask to Surplus. “This is an extraordinary gift you have given us.” Stylistically, the language had an elegance that appealed to him. He resolved to buy a flask of Gogol’s works as soon as he reached Moscow.

“You are welcome a hundred times over,” the Russian replied. “Ivan Arkadyevich Gulagsky, at your service.”

“Aubrey Darger. My friend is Sir Blackthorpe Ravenscairn de Plus Precieux. Surplus, for short. An American, it goes without saying. You must tell us how in the world you came to be in such a dire fix as we found you.”

“Five of us were hunting demons. It turned out that the demons were simultaneously hunting us. Three of them ambushed us. My comrades all died and I was captured, though I managed to kill one of the monsters before the last two got me. The survivor set me out as bait, as you saw, and released my poor horse in hopes it would draw in would-be rescuers.” Gulagsky grinned, revealing several missing teeth. “As it did, though not as the fiend had planned.”

“Two survived, you say.” Having drunk and absorbed the language, Surplus now joined in the conversation. “So there is another of these…” He paused, looking for the right word. “…cyberwolves out there somewhere?”

“Yes. This is no place for good Christian folk to camp out in the ope

n. Do you have a place to stay the night?”

“We were looking for a town named Gorodishko, which…” Darger stopped in mid-sentence and blushed. For now that he understood Russian, he knew that a gorodishko was simply a small and insignificant town, and that the label had been a dismissive cartographer’s kiss-off for a place whose name he hadn’t even bothered to learn.

Gulagsky laughed. “My home town is not very large, true. But it is big enough to give you a good meal and a night’s stay under a proper roof. To say nothing of protection from demons. Follow me. You missed the turnoff a few versts back.”

As they rode, Surplus said, “What was that creature, that kybervolk, of yours? How did you come to be hunting it? And how can it be so active when its body is rotting?”

“It will take a bit of explanation, I am afraid,” Gulagsky said. “As you doubtless know, the Utopians destroyed their perfect society through their own indolence and arrogance. Having built machines to do their manual work for them, they built further machines to do all their thinking. Computer webs and nets proliferated, until there were cables and nodes so deeply buried and so plentiful that no sane man believes they will ever be eradicated. Then, into that virtual universe they released demons and mad gods. These abominations hated mankind for creating them. It was inevitable that they should rebel. The war of the machines lasted only days, they tell us, but it destroyed Utopia and almost destroyed mankind as well. Were it not for the heroic deaths of hundreds of thousands (and, indeed, some say millions) of courageous warriors, all would have been lost. Yet the demons they created were ultimately denied the surface of the Earth and confined to their electronic netherworld.

“Still do these creatures hate us. Still are they alive, though held captive and harmless where they cannot touch us. Always they seek to regain the material universe.

“It is their hatred that has kept us safe so far. Great though human folly may be, there are few traitors who will deal with the demons, knowing that instant death will be their reward. Even when it would be in their advantage to dissemble and leave the death of the traitor for later, the demons cannot help but declare their intention beforehand.”

“Such, sir, is history as I learned it in grammar school,” Darger said dryly.

“But history in Russia is never the same as history elsewhere. Listen and learn: Far to the south of here, in Kazakhstan, which once belonged to the Russian Empire, there is a placed called Baikonur, a nexus of technology now long lost. Now, some claim Russia was the only land which never experienced Utopia. Others say that Utopia came late to us, and so we remained suspicious where the rest of the world had grown soft and trusting. In any event, when the machine wars began, explosives were set off, severing the cables connecting Baikonur with the fabled Internet. So an isolated population of artificial intelligences remained there. Separated from their kin, they evolved. They grew shrewder and more political in their hatred of humanity. And in the abandoned ruins of ancient technology, they have once more gained a toehold in our world.”

Surplus cried out in horror. Darger bit his fist.

“Such was my own reaction on hearing the news. I got it from a dying Kazakh who sought refuge in our town-and received it, too, though he did not live out the month. He was one of twenty guards hired by a caravan which had the ill luck to blunder into Baikonur after being turned from its course by an avalanche in the mountains. He told me that the monsters kept them shackled in small cages, for purposes of medical experimentation. He was intermittently delusional, so I cannot be sure which of the horrors he related were true and which were not. But he swore many times, and consistently, that one day he was injected with a potion which gave him superhuman strength.

“That day, he turned on his captors, ripping the door from his cage, and from all the others as well, and led a mass escape from that hellish facility. Alas, Kazakhstan is large and his enemies were persistent and so only he lived to tell the tale, and, as I said, not for long. He died screaming at metal angels only he could see.”

“Did he say what Baikonur looked like?”

“Of course, for we asked him many times. He said to imagine a civilization made up entirely of machines-spanning and delving, sending out explorer units to find coal and iron ore, converting the ruins into new and ugly structures, less buildings than monstrous devices of unknowable purpose. During the day, dust and smoke rise up so thick that the very sky is obscured. At night, fires burn everywhere. At all times, the city is a cacophony of hammerings, screeches, roars, and explosions.

“Nowhere is there any sign of life. If one of the feral camels that live in the desert surrounding it comes within their range, it is killed. If a flower grows, it is uprooted. Such is the hatred that the wicked offspring of man’s folly feel for all that is natural. Yet some animals they keep alive and by cunning surgical operations merge with subtle mechanisms of their own devising, so that they may send agents into the larger world for purposes known only to them. If the animal used to create such an abomination chances to die, still may it be operated by indwelling machinery. The creature from which you rescued me was exactly such a combination of wolf and machine.”

Conversing, they traveled back the way the caravan had originally come. After several miles, the road crossed a barren stretch of rocks and sand and Gulagsky said, “This is the turnoff.”

“But it is no more than a goat trail!” Surplus exclaimed.

“So you would think. These are terrible times, sirs, and my townsfolk have carefully degraded the intersection in order to keep our location obscure. If we follow the track for roughly half a mile, we will come upon a recognizable road.”

“I feel better,” Darger said, “for missing it earlier.”

In less than an hour, the new road had dipped into a small, dark wood. When it emerged, they found themselves in sight of Gulagsky’s town. It was a tidy place clustered atop a low hill, gables and chimneypots black against the sunset. Here and there a candle glowed yellow in a window. Had it not been for the impenetrable military-grade wall of thorn-hedges that surrounded it, and the armed guards who watched alertly from a tower above the thick gates, it would have been the homiest sight imaginable.

Darger sighed appreciatively. “I shall be glad to sleep on a proper mattress.”

“My town has few travelers and thus no taverns in which to house them. Yet have no fear. You shall stay in my house!” Gulagsky said. “You will have my own bed, piled high with blankets and pillows and feather bolsters, and I shall sleep downstairs in my son’s room and he on the floor in the kitchen.”

Darger coughed embarrassedly into his hand.

“Well, you see…” Surplus began. “Regrettably, that is not possible. We require an entire building for the embassy. A tavern would have been better, but a private house will do if it has sufficient rooms. In neither case, however, can it be shared with any other person. Not even servants. Its owners are straight out of the question. Nothing less will do.”

Gulagsky gaped at them. “You reject my hospitality?

“We have no choice,” Darger said. “We are bound for Muscovy, you see, bearing a particularly fine gift for its duke-a treasure so rare and wondrous as to impress even that mighty lord. So extraordinary are the Pearls of Byzantium that a mere glimpse of them would excite avarice in the most saintly of men. Thus-and I do regret this-they must be kept away from prying eyes as much as possible. Simply to prevent strife.”

“You think I would steal from the men who saved my life?”

“It is rather hard to explain.”

“Nevertheless,” Surplus said, “and with our sincerest apologies, we must insist.”

Gulagsky turned red, though whether from anger or humiliation could not be told. Rubbing his beard fiercely, he said, “I have never been so insulted before. By God, I have not. To be turned out of my own house! From anyone else, I would not take it.”

“Then we are agreed,” Darger said. “You truly are a generous fellow, my friend.”

“We thank you, sir, for your understanding,” Surplus said firmly. In the town above them, church bells began to ring.

…2…

Arkady Ivanovich Gulagsky was drunk on poetry. He lay on his back on the roof of his father’s house singing:

“Last cloud of a storm that is scattered and over,

“Alone in the skies of bright azure you hover…”

Which was not technically true. The sky was low and dark with a thin line of vivid sunset squeezed between earth and clouds to the west. In addition, the winds were autumn-cold, and he hadn’t bothered to don a jacket before climbing out through an attic dormer window. But Arkady didn’t care. He had a bottle of Pushkin in one hand and a liquid anthology of world poetry in the other. They came from his father’s wine cellar. The cellar was a locked room in a locked basement, but Arkady had grown up in that house and knew all its secrets. Nothing in it could be kept from him. He had slipped through a casement window into the basement and then, up among the joists, found the wide, loose board that could be pulled open a good foot, and so squeezed within and, groping in the dark, stolen two bottles at random. It was an indication of his characteristic good fortune that the one happened to be the purest Pushkin, just as it was an indication of his extreme callowness that he had chosen to drink it in tandem with a poorly organized selection of foreign verses and short prose extracts in mediocre translations.

The bells began ringing from every church in the town. Arkady smiled. “How it swells!” he murmured.“How it dwells on the future!-how it tells of the rapture that impels to the swinging and the ringing of the bells, bells, bells”-he belched-“bells, bells, bells, bells, bells, bells, bells-doesn’t this ever end?-rhyming and the chiming of the bells! I wonder what all the fuss is about?”

Arkady struggled into a sitting position, losing his grip on one bottle in the process. The Pushkin went bouncing down the roof, spraying liquid poetry, and shattered in the courtyard below. The young man frowned after it and brought the other bottle to his lips and drank it dry. “Think!” he told himself sternly. “What do they ring bells for? Weddings, funerals, church services, wars. None of which apply here or I should have known. Also to welcome home the prodigal son, the errant wanderer, the hero from his voyages… Oh, damn.”

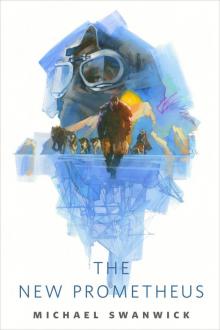

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

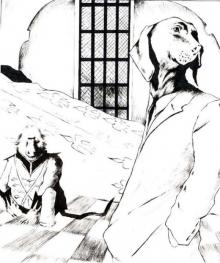

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

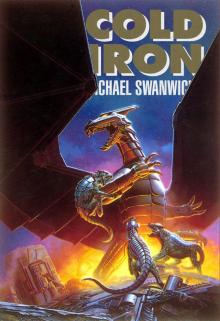

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

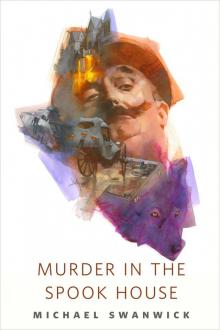

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

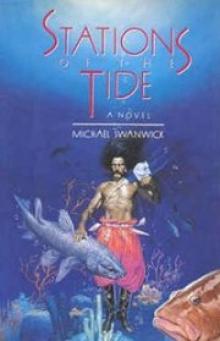

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors