- Home

- Michael Swanwick

A Midwinter's Tale Page 2

A Midwinter's Tale Read online

Page 2

It was the solstice, and the moons were full -- a holy time. I felt it even as I fled the woman through the wilderness. The moons were bright on 1 the snow. I felt the dread of being hunted descend on me, and in my inarticulate way I felt blessed.

But I also felt a great fear for my kind. We had dismissed the humans as incomprehensible, not very interesting creatures, slow-moving, badsmelling, and dull-witted. Now, pursued by this madwoman on her fast machine, brandishing a weapon that killed from afar, I felt all natural order betrayed. She was a goddess of the hunt, and I was her prey.

The People had to be told.

I gained distance from her, but I knew the woman would catch up. She was a hunter, and a hunter never abandons wounded prey. One way or another, she would have me.

In the winter, all who are injured or too old must offer themselves to the community. The sacrifice rock was not far, by a hill riddled from time beyond memory with our burrows. My knowledge must be shared: The humans were dangerous. They would make good prey.

I reached my goal when the moons were highest. The flat rock was bare of snow when I ran limping in. Awakened by the scent of my blood, several People emerged from their dens. I laid myself down on the sacrifice rock. A grandmother of the People came forward, licked my wound, tasting, considering. Then she nudged me away with her forehead. The wound would heal, she thought, and winter was young; my flesh was not yet needed.

But I stayed. Again she nudged me away. I refused to go. She whined in puzzlement. I licked the rock.

That was understood. Two of the People came forward and placed their weight on me. A third lifted a paw. He shattered my skull, and they ate.

Magda watched through power binoculars from atop a nearby ridge. She saw everything. The rock swarmed with lean black horrors. It would be dangerous to go down among them, so she waited and watched the puzzling tableau below. The larl had wanted to die, she’d swear it, and now the beasts came forward daintily, almost ritualistically, to taste the brains, the young first and then the old. She raised her rifle, thinking to exterminate a few of the brutes from afar.

A curious thing happened then. All the larls that had eaten of her prey’s brain leaped away, scattering. Those that had not eaten waited, easy targets, not understanding. Then another dipped to lap up a fragment of brain, and looked up with sudden comprehension. Fear touched her.

The hunter had spoken often of the larls, had said that they were so elusive he sometimes thought them intelligent. "Come spring, when I can afford to waste ammunition on carnivores, I look forward to harvesting a few of these beauties," he’d said. He was the colony’s xenobiologist, and he loved the animals he killed, treasured them even as he smoked their flesh, tanned their hides, and drew detailed pictures of their internal organs. Magda had always scoffed at his theory that larls gained insight into the habits of their prey by eating their brains, even though he’d spent much time observing the animals minutely from afar, gathering evidence. Now she wondered if he were right.

Her baby whimpered, and she slid a hand inside her furs to give him a breast. Suddenly the night seemed cold and dangerous, and she thought: What am I doing here? Sanity returned to her all at once, her anger collapsing to nothing, like an ice tower shattering in the wind. Below, sleek black shapes sped toward her, across the snow. They changed direction every few leaps, running evasive patterns to avoid her fire.

"Hang on, kid," she muttered, and turned her strider around She opened up the throttle.

Magda kept to the open as much as she could, the creatures following her from a distance. Twice she stopped abruptly and turned her rifle on her pursuers. Instantly they disappeared in puffs of snow, crouching belly-down but not stopping, burrowing toward her under the surface In the eerie night silence, she could hear the whispering sound of the brutes tunneling. She fled.

Some frantic timeless period later -- the sky had still not lightened in the east -- Magda was leaping a frozen stream when the strider’s left ski struck a rock. The machine was knocked glancingly upward, cybernetics screaming as they fought to regain balance. With a sickening crunch, the strider slammed to earth, one ski twisted and bent. It would take extensive work before the strider could move again.

Magda dismounted. She opened her robe and looked down on her child. He smiled up at her and made a gurgling noise.

Something went dead in her.

A fool. I’ve been a criminal fool, she thought. Magda was a proud woman who had always refused to regret, even privately, anything she had done. Now she regretted everything: Her anger, the hunter, her entire life, all that had brought her to this point, the cumulative madness that threatened to kill her child.

A larl topped the ridge.

Magda raised her rifle, and it ducked down. She began walking downslope, parallel to the stream. The snow was knee deep and she had to walk carefully not to slip and fall. Small pellets of snow rolled down ahead of her, were overtaken by other pellets. She strode ahead, pushing up a wake.

The hunter’s cabin was not many miles distant; if she could reach it, they would live. But a mile was a long way in winter. She could hear the larls calling to each other, soft cough-like noises, to either side of the ravine. They were following the sound of her passage through the snow. Well, let them. She still had the rifle, and if it had few bullets left, they didn’t know that. They were only animals.

This high in the mountains, the trees were sparse. Magda descended a good quarter-mile before the ravine choked with scrub and she had to climb up and out or risk being ambushed. Which way? she wondered. She heard three coughs to her right, and climbed the left slope, alert and wary.

We herded her. Through the long night we gave her fleeting glimpses of our bodies whenever she started to turn to the side she must not go, and let her pass unmolested the other way. We let her see us dig into the distant snow and wait motionless, undetectable. We filled the woods with our shadows. Slowly, slowly, we turned her around. She struggled to return to the cabin, but she could not. In what haze of fear and despair she walked! We could smell it. Sometimes her baby cried, and she hushed the milky-scented creature in a voice gone flat with futility. The night deepened as the moons sank in the sky. We forced the woman back up into the mountains. Toward the end, her legs failed her several times; she lacked our strength and stamina. But her patience and guile were every bit our match. Once we approached her still form, and she killed two of us before the rest could retreat. How we loved her! We paced her, confident that sooner or later she’d drop.

It was at night’s darkest hour that the woman was forced back to the burrowed hillside, the sacred place of the People where stood the sacrifice rock. She topped the same rise for the second time that night, and saw it. For a moment she stood helpless, and then she burst into tears.

We waited, for this was the holiest moment of the hunt, the point when the prey recognizes and accepts her destiny. After a time, the woman’s sobs ceased. She raised her head and straightened her back.

Slowly, steadily, she walked downhill.

She knew what to do.

Larls retreated into their burrows at the sight of her, gleaming eyes dissolving into darkness. Magda ignored them. Numb and aching, weary to death, she walked to the sacrifice rock. It had to be this way.

Magda opened her coat, unstrapped her baby. She wrapped him deep in the furs. and laid the bundle down to one side of the rock. Dizzily, she opened the bundle to kiss the top of his sweet head, and he made an angry sound. "Good for you, kid," she said hoarsely. "Keep that attitude." She was so tired. ~.

She took off her sweaters, her vest, her blouse. The raw cold nipped at her flesh with teeth of ice. She stretched slightly, body aching with motion. God it felt good. She laid down the rifle. She knelt.

The rock was black with dried blood. She lay down flat, as she had earlier seen her larl do. The stone was cold, so cold it almost blanked out the pain. Her pursuers waited nearby, curious to see what she was doing; she could hear the soft pantin

g noise of their breathing. One padded noiselessly to her side. She could smell the brute. It whined questioningly.

She licked the rock.

Once it was understood what the woman wanted, her sacrifice went quickly. I raised a paw, smashed her skull. Again I was youngest. Innocent, I bent to taste.

The neighbors were gathering, hammering at the door, climbing over one another to peer through the windows, making the walls bulge and breathe with their eagerness. I grunted and bellowed, and the clash of silver and clink of plates next door grew louder. Like peasant animals, my husband’s people tried to drown out the sound of my pain with toasts and drunken jokes.

Through the window I saw Tevin-the-Fool’s bonewhite skin gaunt on his skull, and behind him a slice of face -- sharp nose, white cheeks -- like a mask. The doors and walls pulsed with the weight of those outside. In the next room, children fought and wrestled, and elders pulled at their long white beards, staring anxiously at the closed door.

The midwife shook her head, red lines running from the corners of her mouth down either side of her stern chin. Her eye sockets were shadowy pools of dust. "Now push!" she cried. "Don’t be a lazy sow!"

I groaned and arched my back. I shoved my head back and it grew smaller, eaten up by the pillows. The bedframe skewed as one leg slowly buckled under it. My husband glanced over his shoulder at me, an angry look, his fingers knotted behind his back.

All of Landfall shouted and hovered on the walls.

"Here it comes!" shrieked the midwife. She reached down to my bloody crotch, and eased out a tiny head, purple and angry, like a goblin.

And then all the walls glowed red and green and sprouted large flowers. The door turned orange and burst open, and the neighbors and crew flooded in. The ceiling billowed up, and aerialists tumbled through the rafters. A boy who had been hiding beneath the bed flew up laughing to where the ancient sky and stars shone through the roof.

They held up the child, bloody on a platter.

Here the larl touched me for the first time, that heavy black paw like velvet on my knee, talons sheathed. "Are you following this?" he asked. "Can you separate truth from fantasy, tell what is fact and what the mad imagery of emotions we did not share? No more could I. All that, the first birth of human young on this planet, I experienced in an instant. Blind with awe, I understood the personal tragedy and the communal triumph of that event, and the meaning of the lives and culture behind it. A second before, I lived as an animal, with an animal’s simple thoughts and hopes. Then I ate of your ancestor and was lifted all in an instant halfway to godhood.

"As the woman had intended. She had died thinking of the child’s birth, in order that we might share in it. She gave us that. She gave us more. She gave us language. We were wise animals before we ate her brain, and we were People afterward. We owed her so much. And we knew what she wanted from us." The larl stroked my cheek with his great, smooth paw, the ivory claws hooded but quivering slightly, as if about to awake.

I hardly dared breathe.

"That morning I entered Landfall, carrying the baby’s sling in my mouth. It slept through most of the journey. At dawn I passed through the empty street as silently as I knew how. I came to the First Captain’s house. I heard the murmur of voices within, the entire village assembled for worship. I tapped the door with one paw. There was sudden, astonished silence. Then slowly, fearfully, the door opened."

The larl was silent for a moment. "That was the beginning of the association of People with humans. We were welcomed into your homes, and we helped with the hunting. It was a fair trade. Our food saved many lives that first winter. No one needed know how the woman had perished, or how well we understood your kind.

"That child, Flip, was your ancestor. Every few generations we take one of your family out hunting, and taste his brains, to maintain our closeness with your line. If you are a good boy and grow up to be as bold and honest, as intelligent and noble a man as your father, then perhaps it will be you we eat."

The larl presented his blunt muzzle to me in what might have been meant as a friendly smile. Perhaps not; the expression hangs unreadable, ambiguous in my mind even now. Then he stood and padded away into the friendly dark shadows of the Stone House.

I was sitting staring into the coals a few minutes later when my secondeldest sister -- her face a featureless blaze of light, like an angel’s -- came into the room and saw me. She held out a hand, saying, "Come on, Flip, you’re missing everything." And I went with her.

Did any of this actually happen? Sometimes I wonder. But it’s growing late, and your parents are away. My room is small but snug, my bed warm but empty. We can burrow deep in the blankets and scare away the cave-bears by playing the oldest winter games there are.

You’re blushing! Don’t tug away your hand. I’ll be gone soon to some distant world to fight in a war for people who are as unknown to you as they are to me. Soldiers grow old slowly, you know. We’re shipped frozen between the stars When you are old and plump and happily surrounded by grandchildren, I’ll still be young, and thinking of you. You’ll remember me then, and our thoughts will touch in the void. Will you have nothing to regret? Is that really what you want?

I thought once that I could outrun the darkness. I thought -- I must have thought -- that by joining the militia I could escape my fate. But for all that I gave up my home and family, in the end the beast came anyway to eat my brain. Now I am alone. A month from now, in all-this world, only you will remember my name. Let me live in your memory.

Come, don’t be shy. Let’s put the past aside and get on with our lives. That’s better. Blow the candle out, love, and there’s an end to my tale.

All this happened long ago, on a planet whose name has been burned from my memory. --

FB2 document info

Document ID: 5d4d362b-6bfd-1014-b814-ee96f15a91af

Document version: 1

Document creation date: 03.06.2008

Created using: Text2FB2 software

Document authors :

traum

About

This file was generated by Lord KiRon's FB2EPUB converter version 1.1.5.0.

(This book might contain copyrighted material, author of the converter bears no responsibility for it's usage)

Этот файл создан при помощи конвертера FB2EPUB версии 1.1.5.0 написанного Lord KiRon.

(Эта книга может содержать материал который защищен авторским правом, автор конвертера не несет ответственности за его использование)

http://www.fb2epub.net

https://code.google.com/p/fb2epub/

Michael Swanwick, A Midwinter's Tale

Thank you for reading books on Archive.BookFrom.Net

Share this book with friends

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

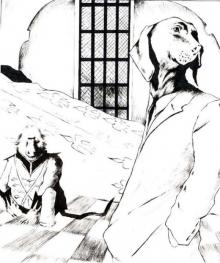

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors