- Home

- Michael Swanwick

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Page 2

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Read online

Page 2

I sank to my knees before the margrave and, taking his hands in mine, cried, “Sir, you must not entertain such evil thoughts as I see in your mind. The world is a dark place, but it would be darker still without your presence. I pray you, do not follow Werther’s path to self-destruction.”

The margrave looked surprised. Then he said, “I keep forgetting what a remarkable young fellow you are. So you can read my thoughts? I should not be surprised. But be comforted. Even that mode of escape is forbidden me. Willingly or not, I must be faithful to your father—and since he desires that I live, so I shall.”

“Then we are returned to our eternal colloquy: Whether or not there is free will and, if there is, why it is denied to the likes of us.”

“It can hardly be called eternal,” the margrave said with a touch of amusement, “for we have only known each other for a month. But, yes, we have had this discussion before.”

Caught in a turmoil of emotions such as would require a Goethe to describe, I blurted out, “Tell me. If you were free from all restraints, what would you do?”

“I would scour this castle with fire and kill all within it,” the Margrave said. “Present company excepted, of course.”

“And if that were denied you? What would be your second choice?”

Without hesitation, the margrave replied, “Oblivion.”

My heart sank. I could see his thoughts and knew that my mentor spoke only the simple truth. Wise though he was, the old man was blind to all possibilities save those he had been brought up to esteem. “Alas,” I said, “I had hoped for a different answer.” But respecting the margrave as I did—and, remember, his was the only moral authority I had ever known—I had, I felt, no choice.

Reaching into his mind, I freed him from my father’s control.

* * *

The homunculus lapsed into silence.

After a time, Ritter said, “I’ve heard rumors of what ensued.” Which was a lie, for they had been formal reports. Then, truthfully, “I had no idea my uncle was involved.”

“There were many wizards in my father’s court. So the margrave was, inevitably, as he knew he would be, killed. Not, however, before having his vengeance. For over an hour, he raged up and down the castle corridors. At the time I thought I had done the right thing. Yet it deprived my world of the only being I knew to be worthy of admiration. Even today, I wonder. Does freedom inevitably entail death? Freeing the margrave was the act of a young and inexperienced man. I regret it now.

“I am sorry, Ritter.”

“Don’t be,” Ritter said. “My uncle labored chiefly as a diplomat. But like all the men of my family, he was at heart a soldier. He died a warrior’s death. That is good to hear. What did you do next?”

* * *

I fled, with the castle burning behind me. On my way out of the city, I encountered a Swedish merchant returning from Russia with a short wagon train of goods and bought passage with him (or, rather, put the memory of my having paid him in his mind) to Helsinki. He was a fat, ugly, vulgar little man—the first words he ever said to me were, “Pull my finger,” and he roared when I did—yet I found I liked him quite a lot, for he was utterly free of malice. He talked frequently of his wife, whom he sincerely loved, though that did not prevent him from frequenting brothels while he was on the road. Such a specimen was he! So different from the models of my reading.

Old Hannu was a merchant through and through. It was a kind of religion to him. He spoke often of its virtues: “Each man benefits,” he said. “Mark that! I buy lace in Rauma, to the enrichment of those who make it, sell it in St. Petersburg to shopkeepers who immediately double its price, and with the proceeds buy furs from Siberian trappers, who are grateful for my money. Both lace and furs multiply in value through the mere expedient of bringing them elsewhere. Midway between, I buy amber and silver jewelry to be sold in both directions. At every step, I make a profit, as do those I buy from and sell to.

“People speak harshly of merchants because we drive a hard bargain. And it’s true I squeeze the buyers until they shit gold. Yet at the end of the day, everyone goes home satisfied. If there is a magic greater than this, I’m damned if I know of it. Did the Apostle Paul make half so many people happy as I have? Bugger me with a mule if he did.”

When I booked passage with Old Hannu, I had deemed it necessary to pay with fairy gold, for I was penniless and in desperate straits. Traveling with the merchant, however, I came to see that I had cheated this cheerful, awful, self-serving little man as he would never have cheated me. With a shock that was almost physical, I realized that, once again, I had sinned … For which I must atone.

So it was that the next time we came to a city, I accompanied Old Hannu to a tavern where women sold themselves. I did not partake in the pleasures of the flesh, however. Instead, I got into a card game with two professional cheats and a compulsive gambler.

I won everything the three men had. Two of them followed me out onto the street and in the shadows set upon me with cudgels. I could have broken their bodies. Instead, I placed in their minds an awareness of the precariousness of their position: that they were landless men outside the protection of the law, outnumbered and hated by the righteous and yet easy prey to men even more wicked than they. Then I set fire to their cudgels and watched them flee into the outer darkness. Perhaps they reformed their evil ways. If not, I am sure that they practice their illicit trade a great deal more circumspectly than before.

The compulsive gambler I trailed at a distance. He came to a church and, going in, climbed the long spiral stair to the top of the steeple. There, he gripped the stone balustrade with fear-whitened hands, building up his courage to throw himself over. He did not hear me coming up behind him. It gave him a start when I spoke, but that was all to the good. Returning half his money, I said, “You have learned a hard lesson tonight, my friend. Go home and never gamble again.” And I erased the compulsion from his mind.

Thus it went, step by step, for larger and smaller sums. In Lublin, I saved a dowager’s fortune from a venal lawyer and he was fined to pay for my efforts. While stopping at a farmhouse, I uncovered a buried Viking hoard, for which I accepted a modest finder’s fee. Sometimes my actions were legal and other times not. But every one of them ended with the other party better off than before. As Old Hannu would have put it, I gave good weight. And, bit by bit, I paid him back every pin of what I owed him.

Occasionally, men tried to kill me. I made them less murderous and sent them back to their masters.

* * *

We came at last, after long and ordinary hardships, to Helsinki. Old Hannu brought me home to meet his family.

Doubtless, you will be nowhere near so dumbstruck as I was to learn that Old Hannu’s wife Leena was in no way the paragon of beauty and virtue he had made her out to be. She was, in her way, as ugly as he. Worse, as I was headed for the outhouse, she ambushed me, rubbing her body against mine in a manner no respectable housewife would. “I’m no beauty,” she said, “and I know it. But lie down with me and close your eyes and you’ll swear I’m as delightful as any of those Russian whores my husband won’t shut up about.” It would have made a dog laugh to see the convolutions I went through to evade her intentions.

Yet for all that, the love Leena and Old Hannu had for each other was genuine. I saw it in their glances, heard it in their speech, witnessed it in their deeds, and of course read it in their thoughts.

Further, they had a daughter.

Kaarina was as pious, virtuous, and chaste as Werther’s beloved Charlotte, and as beauteous as her father imagined her mother to be. I was smitten. When her parents invited me to stay on for a time, I did, just to be near her.

You will scarcely believe this, but Kaarina did not see me as hideous at all. Perhaps this was because her love for animals—she was forever rescuing kittens and fostering crippled dogs—caused her to see me not as a caricature of humanity but simply as one of God’s creatures. For a time, I was content merely being

a part of her world, worshipping her from afar.

Then, one day in the garden, Kaarina invited me to sit down beside her. “You are always so silent,” she said. “When you first arrived, I thought you a mute. Tell me something of yourself.”

I needed no urging. All my thoughts, dreams, hopes, fears, loftiest aspirations, and meanest deeds came pouring out of me in a torrent of words. I shared my innermost self as I never had before nor ever would again, save right now with you, holding back only my feelings for Kaarina herself, lest she be alarmed by them. And when I was done…

Kaarina looked at me in blank bewilderment.

“But none of this makes any sense,” she said. “A child born without a mother and grown to man’s estate in a matter of months. A nonpareil who teaches himself to read in an afternoon but kills his instructor on a whim. A redeemer of widows and gamblers who steals from an honest merchant. A master of all magics who has neither wealth nor position. A demigod who can read thoughts but suffers from doing so. How could such a living contradiction even exist? What place could he possibly find for himself in human society? You must clear your head of these dark fantasies and strive to be restored to your true self.”

Kaarina was not angry at me—her character was too refined for that. Nevertheless, her words cut through me like so many knives. I was her physical and intellectual superior and knew it. But our emotions are seated in the body and the body is an animal, even as the bear or the ass. In this regard I am in no way superior to any other man, nor will I ever be, however much my mental powers may increase.

My passion got the better of me.

“But every word I spoke was true!” I cried and, throwing caution to the winds, added, “Furthermore…”

Seeing my distress, Kaarina took my great hand in her wee paws and said, “You may speak your mind freely, my friend. There is nothing you cannot tell me.”

“Then I will say it—I love you.”

May you never see such a look on the face of a woman you esteem! Kaarina’s mouth fell open with astonishment and horror. There could be no mistaking the latter emotion, for I saw it burning in her thoughts like a flare.

I flushed red with humiliation. My blood surged and my hands clenched with the desire to strike Kaarina, to hurt her, to punish her for not loving me. It lasted only a single horrifying instant. Then, overcome with confusion and remorse, I fled. Kaarina, I am sure, prayed for my welfare and the rapid recovery of my wits. As if that would help!

That night, lying abed in the guest room (with the dresser pushed against the door, in case Leena again decided to make an assault upon my virtue), I thought over everything I had gone through and learned since coming to Helsinki. It had just been forcibly demonstrated that there could be no future for Kaarina and me. I needed love, not pity! And she … needed someone she could understand. My feelings for her were undiminished. But, alas, there could be no true communion of thought between us. The imbalance of intellect was simply too great.

It was a painful process working this out while the thoughts of the city roared and crashed over me like a mighty surf. But I came at last to two conclusions. First, that I could not stay in this house a day longer. Second, that in order to adequately think through my life and purpose, I must somehow isolate myself completely from humanity.

In the morning, profusely thanking Old Hannu for his hospitality, I left. Then I set about outfitting an expedition to the unknown Arctic regions. Out of respect for the values of the man I considered the second great mentor of my life, I earned the tremendous sum this required by honest means.

Which was why you almost caught up with me before my ship sailed.

* * *

As the ship left the harbor, the eternal pandemonium of thoughts faded and I had to endure only those of the Erebus’s officers and crew. I wept with relief. So you can imagine with what ecstasy I beheld the icy shores of this desolate land. And when the ship sailed off, carrying away with it the last trace of any thought other than my own, I experienced a sensation of pure bliss. Oh, blessed silence! I fell to my knees to thank whatever gods may be for that wondrous gift. Then, carrying all my supplies on my back, I walked inland until I judged myself safe from the influence of any passing ship. There I sat down and proceeded to think. To think, and to plan.

My first conclusion was that I needed a mate—one every bit as beautiful and virtuous as Kaarina but also as intelligent and strong of body as I. There being no such woman, I would have to create her myself. Which would be no easy task. To build such a goddess would require the use of many wizards, the sacrifice of numerous animals and women, and a fortune in related materials. Vast wealth would be required. Further, since such a project could not possibly be kept secret, it would demand defenses: an army, a secure territory with fortified borders, and a system of secret police to protect me from spies and saboteurs. In short, it would entail exactly such an empire as my father is currently endeavoring to create. For a moment, I was aghast at the thought of what atrocities I would have to perform.

Then I resolved to do it. My mate and I would wed and have children who would have children in their turn and their descendants would inevitably supplant the human race. All the world would be theirs and I their Adam.

You blanch, Ritter. Be reassured. My resolution lasted but a moment. For I then reflected that to carry out my plan would be to expose a woman I hoped to love with unswerving dedication to the pain of hearing the thoughts of Mankind which had almost driven me mad. Yes, I could immediately upon her creation put to death all those involved, before her capacity to hear their thoughts came into focus and then carry her off to some desolate tract such as this. But what would happen when she could read my thoughts? When she understood what crimes I had committed in her not-so-immaculate conception?

Logic, alas, told me that the project was doomed to fail.

Thus: No wife, no offspring, no hope, no future.

I had just determined what course of action I should take when I sensed your approach. It occurred to me then that it would be pleasant to share the tale of my life with a sympathetic soul. From what I could sense of your character, it seemed to me that you might well understand my story.

So I let you approach.

* * *

For a long time, the homunculus did not speak. Ritter, who was comfortable with silence, waited. At last his host said, “Have you ever considered beetles, Ritter?”

“Beetles,” Ritter said flatly. “No, not since I was a boy.”

“They are, I assure you, fascinating creatures and well worthy of your respect. But they cannot provide much in the way of companionship.” The homunculus stood. “On which note, the time has come to put an end to our colloquy.”

Ritter tried to stand and discovered that he could not. Nor could he move so much as a finger though his lungs, for a mercy, continued to pump air.

The creature looked down on him with an expression of gentle pity. “You are not a good man, Ritter. How could you be, given your occupation? However, you are not as bad a man as you fear you might be—not yet, at any rate.” He went outside, leaving the tent flap open behind him. Over his shoulder, he said, “Imperfect though you are, I wish you well. I wish every single one of you well. But I cannot bear to live among you.”

The homunculus walked steadily away from the tent, toward a distant ridge. When sufficient time had elapsed, he passed over the ridge and out of sight. All the while, Ritter strove in vain to cast off his paralysis. Nor could he enter Freki’s mind—that ability too, it seemed, had been frozen.

Then the sun came up.

There was a tremendous light, at which Ritter discovered himself capable of movement again, for he automatically turned away from it and threw up an arm to protect his eyes. Almost immediately, there followed a sound so thunderous that he clapped his hands over his ears to reduce it to a roar.

Ritter burst from the tent.

Running with all his might, Freki at his heels, he came to the top of the ridge

over which the creature had disappeared. Below him Ritter saw a crater half-blasted and half-melted into the ice with a smudge of black at its center, as if a god had reached down from the sky to brush a dirty fingertip against the snow.

* * *

When Ritter had done making his report, Sir Toby said, “It is a pity you could not win him over to our cause.”

“In his estimation, our cause was not a good one. I do not believe that the creature saw very much difference between our side and his father’s.”

A darkness congealed within Sir Toby then, as if there were a thunderhead filling his skull and threatening to burst through it with gales and lightning. But he only said, “And who was he to pass judgment on us? The ugly brute!”

“No. He was a handsome man, very much so. By any reasonable definition, he was extremely well made.” Ritter shook his head sadly. “Yet in his own eyes, he was monstrous.”

About the Author

Michael Swanwick is the winner of five Hugo Awards for his short fiction. His several novels include the Nebula-winning Stations of the Tide, the time-travel novel Bones of the Earth, and the “industrial fantasy” novels The Iron Dragon’s Daughter and The Dragons of Babel. He lives in Philadelphia. You can sign up for email updates here.

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

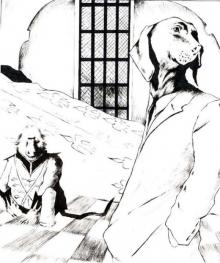

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors