- Home

- Michael Swanwick

Day of the Kraken Page 2

Day of the Kraken Read online

Page 2

“He says ‘Me!’” the redheaded girl said, and “Me! Me!” the others cried in imitation of her.

“Yes, he does. He runs around and around in tight little circles, barking yip! yip! yip! That means me! me! me!”

“Do you give him the treat then?” the smallest and shyest asked.

Ritter made a mock indignant face. “Of course I do. Who could turn down a poor sweet hungry wolf like that? Not I!”

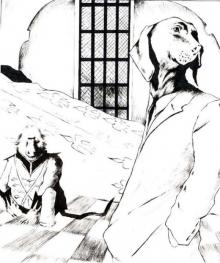

By now two of the girls had climbed into Ritter’s lap and the others were clustered close around him. He wrapped his arms around them, gently drawing them closer, and went on talking about Freki: How smart he was and how brave. How fast he could run, and how silently. The girls grew still as he described the wolf hunting a rabbit in the forest: Tracking it by scent. Spotting its tail bouncing before him. The sudden burst of speed as he caught up to it. And then, crunch, snap, and gobble.

“Can you lift your paw like Freki?” They all could. “Can you pretend to lick off the blood the way he does?” They all did.

Speaking softly, Ritter drew the little girls into the world of the wolf. He guided them as they pretended to be wolves themselves. And as their thoughts became more and more lupine, he began to ease his own thoughts into theirs.

It was not easy, for he had never tried to enter a human mind before—for both moral and practical reasons, it had been strictly forbidden by his instructors. But he knew, from certain smutty rumors of forced seductions and young officers stripped of rank and familiar just before being summarily executed, that it was not impossible.

And the more the girls thought like wolves, the less impossible it became.

Ritter was not a sentimental man. He prided himself on having few delusions. Yet even he was shocked at how easily the children entered into the amoral and ruthless mind-set of the wolf. He was, it was true, urging them in that direction with both his words and his thoughts. But still. It was alarming how little distinction there was between a young girl and a savage predatory beast.

So deeply involved was Ritter in his task that he almost missed the clatter in the chapel of brushes and buckets of paint being flung away. He kept talking, softly and soothingly, as footsteps sounded in the hall. All of his captors at once, by the sound of it.

A key turned in the lock and Ritter withdrew his arms from the little girls. “Look, my little Frekis!” he said. “Here comes your prey!”

The door opened and he launched his small wolves, snarling and biting, straight at the throats of the three startled saboteurs.

The premier of Haydn’s War in Heaven earned the refugee Austrian composer a standing ovation that seemed to go on forever. Of course it did. The oratorio depicted a senseless rebellion against the natural order, the unswerving loyalty of the Archangel Michael’s forces in the face of impossible odds, and the ultimate triumph of good over evil when God Himself takes the field on their behalf. The political allegory could not have been more obvious. It depressed Ritter greatly. Still, as music, the piece deserved its plaudits. He noted, as they emerged from St. Paul’s Cathedral, that Sir Toby was humming (off-key, of course) the glorious and chilling chorus that marked Lucifer’s fall:

Hurled headlong flaming from the ethereal sky

With hideous ruin and combustion down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell

In adamantine chains and penal fire…

It did not hurt, of course, that the oratorio had Milton’s glorious language to draw upon.

“Let’s take a stroll by the river,” Sir Toby said. “To digest what we’ve heard.” It was not so much a suggestion as a polite command. Ritter, who had been brought up to understand such subtleties, nodded his compliance.

Two days had passed since Sir Toby had burst into the priory at the head of a small contingent of soldiers, only to discover the corpses of the saboteurs and five blood-sated little girls. So far, he had said nothing about the aftermath. But Ritter could feel it coming.

“Wait out here with Freki for a moment,” Ritter said, and went into a pie shop. When he emerged with a package of beef pasties, they resumed their stroll.

Upon reaching the river, the two men paused to lean against a brick wall above a stone stairway leading down to the Thames. The tide was low and a scattering of basket-carrying mudlarks were probing the silvery muck like so many sandpipers. Merchant ships rode at anchor, sails furled, lanterns at bow and stern, while small boats scuttled back and forth on the water, taking advantage of the last cold gleams of daylight. Ritter set his meat pies down on the wall and waited.

At last, Sir Toby said, “The girls’ parents are uniformly outraged by what you made them do.”

“Their daughters are alive,” Ritter said. “They should be grateful.”

“The trauma can be undone. In many ways, the physick of the mind is more advanced in our modern age than is that of the body. It comes from the prominence of wizardry, I suppose. But the memories will remain—and who knows what will come of those memories as the girls grow into women?”

Ritter turned to face his superior. “Are you criticizing my actions?”

“No, no, of course not,” Sir Toby said. “Only…one could wish that your otherwise admirable ability to improvise was accompanied by a less insouciant attitude regarding what your superiors might have to deal with afterwards. To say nothing of your damnable indifference to the welfare of children.”

“In this, I am only typical of the times.”

Sir Toby looked away from his subordinate and lost himself in contemplation of the river. At last he sighed and turned his back on the Thames. “Well, it turns out I had less to say than I thought I did. The wind is chill and I think it is time we made our way to our respective domiciles.”

They walked in silence for a time. Then Sir Toby said, “You left your meat pies behind. On the wall by the river.”

“Did I? Well, there’s no point to going back after them. Doubtless some mudlark has stolen the package by now.” Ritter imagined an urchin wolfing down the food as ravenously as Freki might, and smiled wanly. Possibly he would come back and lose another package tomorrow.

The river disappeared behind them. Then, remembering a resolution he had made earlier in the day, Ritter cleared his throat. “Sir,” he said. “I have a joke. A priest, a minister, and a rabbi chanced to be riding together in a carriage. Suddenly a highwayman—”

Sir Toby held up a hand. “Oh, Ritter,” he said. “You didn’t think I meant that request literally, did you?”

Copyright (C) 2012 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright (C) 2012 by Gregory Manchess

Books by Michael Swanwick

The Dragons of Babel

Bones of the Earth

Jack Faust

The Iron Dragon’s Daughter

Griffin’s Egg

Stations of the Tide

Vacuum Flowers

In the Drift

SHORT STORY COLLECTIONS

The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Periodic Table of Science Fiction

Cigar-Box Faust and Other Miniatures

A Geography of Unknown Lands

Gravity’s Angels

Moon Dogs

Puck Aleshire’s Abededary

Tales of Old Earth

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors