- Home

- Michael Swanwick

Stations of the Tide Page 3

Stations of the Tide Read online

Page 3

“I knew they thought I’d robbed a brother fugitive. I don’t suppose you know much about the suppression of Whitemarsh?”

“No,” the bureaucrat said.

“Only hearsay,” Chu said. “It’s not exactly the sort of history they teach in school.”

“They should,” the commander said. “Let the children know what government is all about. This was back when the Tidewater was young, and communes and Utopian communities were as common as mushrooms. Harmless, most of them were, pallid things here and gone in a month. But the Whitemarsh cults were different; they spread like marsh-fire. Men and women went naked in public daylight. They would not eat meat. They participated in ritual orgies. They refused to serve in the militia. Factories closed for want of laborers. Crops went unharvested. Children were not properly schooled. Private citizens minted their own coinage. They had no leaders. They paid no taxes. No government would have tolerated it.

“We fell on them with fire and steel. In a single day we destroyed the cults, drove the survivors into hiding, and showed them such horror they would never dare rise again. So you understand that I was in great danger. But I did not show fear. I asked them, did they want the money or not?

“One of the men took the bag, weighed it in his hand. Then, as I had hoped, he slid a handful of coins into each of his trousers pockets. We will divide this evenly, he said. So long as the spirit is alive, Whitemarsh is not dead. He threw me a greasy bundle of herbs, and said sneeringly, This would make a corpse rise, much less your limp little self.

“I dropped the bundle in my lead box and left. At home I beat Ysolt until she bled and threw her out in the street. I waited a week, and then reported to internal security that fugitive cultists were hiding in my area. They ran a scan and found the coins, and with the coins the cultists. I still did not know which specific one had defiled my Ysolt, but they all still held most of the coins, so he had been punished. Oh yes, he had been punished well.”

After a moment’s silence the bureaucrat said, “I’m afraid I don’t follow you.”

“I was sent into Whitemarsh just before it fell. I removed the coinmaker, and used a device my superiors had provided to irradiate his stock. Half of those who escaped our wrath carried their debased coinage with them. They never understood how we found them so easily. But it is observed that many of the men came down with radiation poisoning not long after, and where a man least wishes it. Disgusting sight. I still have the pictures.” He stuck his hands in his trousers pockets and raised his eyebrows. “I fed the potion they gave me to Ysolt’s dog, and it died. So much for the subtlety of wizards.”

“The irradiator is illegal,” the bureaucrat said. “Even planetary government is not allowed to use one. It can do a lot of damage.”

“You see your duty, Оhound of the people! Go to it. The trail is only sixty years cold.” Bergier stared bitterly down at his screens. “I look down at the land, and I see my life mapped out beneath me. We’re coming up on Ysolt’s Betrayal, which is sometimes called Cuckold, and further on is Penelope’s Lapse, then Feverdeath, and Abandonment. At the end of the run is Cape Disillusion, and that accounts for all my wives. I have retreated from the land, but I cannot yet completely leave it. I keep waiting. I keep waiting. For what? Perhaps for daybreak.”

Bergier threw open the shutters. The bureaucrat winced as bright white light flooded in, drowning them all in glory, turning the commander pale and old, the flesh hanging loose on his cheeks. Down below they saw the roofs and towers, spires and one gold dome of Lightfoot rising toward them, bristling with antennae.

“I am the maggot in the skull,” Bergier said deliberately, “writhing in darkness.” The illogic of the remark, and its suddenness, jolted the bureaucrat, and in a shiver of insight he realized that those staring eyes were looking not back at horror but forward. There was a premonition of senility in that slow speech, as if the old commander were staring ahead into a protracted slide into toothless misery and a death no more distinct from life than that line dividing ocean from sky.

As they started from the cabin, the commander said, “Lieutenant Chu, I will expect you to keep me posted. I will be following your progress closely.”

“Sir.” Chu closed the door, and they descended the stairs. She laughed lightly. “Did you notice the lozenges?” The bureaucrat grunted. “Swamp-witch nostrums, supposed to be good for impotence. They’re made out of roots and bull’s jism and all sorts of nasty stuff. No fool like an old fool,” she said. “He never leaves that little cabin, you know. He’s famous for it. He even sleeps there.”

The bureaucrat wasn’t listening. “He’s around here somewhere.” He peered into the darkness, holding his breath, but heard nothing. “Hiding.”

“Who?”

“Your impersonator. The young daredevil.” To his briefcase he said, “Reconstruct his gene trace and build me a locater. That’ll sniff him out.”

“That’s proscribed technology,” the briefcase said. “I’m not allowed to manufacture it on a planetary surface.”

“Damn!”

The air within the envelope was still, but filled with tension. It thrummed with the vibrations of the engines, as alive as a coiled snake. The bureaucrat could feel the false Chu peering at them from the shadows. Laughing.

Chu put a hand on his arm. “Don’t.” Her eyes were serious. “If you get emotionally involved with the opposition, they’ve got you by the balls. Cool off. Maintain your detachment.”

“I don’t—”

“—need to take advice from the likes of me. I know.” She grinned cockily, the swaggering cynic again. “The planetary forces are all corrupt and ineffectual, we’re famous for it. Even so, I’m worth listening to. This is my territory. I know the people we’re up against.”

“Watch yourself, buddy!”

The bureaucrat stepped back as four men hoisted a timber up out of the mud and wrestled it onto a flatbed truck. A chunky woman with red hair stood on the truckbed, working the hoist. The buildings here were as tumbledown a lot as he’d ever seen, unpainted, windows cracked, shingles missing. Crusted masses of barnacles covered their north sides.

The ground felt soft underfoot. The bureaucrat looked mournfully down at his shoes. He was standing in the mud. “What’s going on?” he asked.

A withered old shopkeeper, all but lost in the folds of his clothes, as if he had shrunk or they grown, sat watching from his porch. A silver skull dangled from his left ear, marking him as a former space marine, and a ruby pierced through one nostril made him a veteran of the Third Unification. “Ripping out the sidewalks,” he said glumly. “Genuine sea-oak, and it’s been aging in the ground for most of a century. My granddaddy laid it down back when the Tidewater was young. Cheap as dirt then, but a year from now I can name my price.”

“How do I go about renting a boat?”

“Well, I’ll tell you plain, I don’t see how you can. Not that many boats around now that the docks have been tore out.” He smiled sourly at the bureaucrat’s expression. “They were sea-oak too. Tore ’em out last month, when the railroad went away.”

The bureaucrat glanced uneasily at the Leviathan, dwindling low in the eastern sky. A swarm of midges, either vampire gnats or else barnacle flies, hovered nearby threatening to attack, and then shrank to invisibility as they drew away. The flies, airship, railroad, docks, and walks, all of Lightfoot seemed to be receding from his touch, as if caught up by an all-encompassing ebb tide. Suddenly he felt dizzy, drawn into an airless space where his inner ear spun wildly, and there was no ground underfoot.

With a shout the timber was slammed onto the flatbed. The woman handling the crane joked and chatted with the men in the mud. “You gotta see my fantasia, though. You’ll die when you see it. It’s cut right down to here.”

“Gonna show off the top of your tits, eh, Bea?” one of the men said.

She shook her head scornfully. “Halfway down the nipples. You’re going to see parts of me you never suspected exist

ed.”

“Oh, I suspected something all right. I just never felt called on to do anything in particular about them.”

“Well, you come to the jubilee in Rose Hall tomorrow night, and you can eat your heart out.”

“Oh, is that what you want me to eat out?” He grinned wryly, then danced back as the beam slipped a few inches in its harness. “Watch that side there! A little remark like that don’t deserve to get my toes crushed.”

“Don’t you worry. It’s not your toes I’m thinking of crushing.”

“Excuse me,” the bureaucrat called up. “Is there any chance I can rent your truck? Are you the owner?”

The redheaded woman looked down at him. “Yeah, I’m the owner,” she said. “You don’t want to rent this thing, though. See, I’m running it from a battery rated for a rig twice this size, so I gotta step down the voltage, okay? Only the transformer’s going. I can get maybe a half hour out of it before it overheats and starts to melt the insulation. I been kind of nursing it along. Now Anatole’s got a spare transformer, but he thinks he oughta be able to charge an arm and a leg for it. I been holding off. I figure it gets a little closer to jubilee, he’ll take what he can get.”

“Aniobe, I keep telling you,” the shopkeeper said. “I could buy that sucker off him for half what—”

She tossed her head. “Oh, shut up, Pouffe. Don’t you go spoiling my fun!”

The bureaucrat cleared his throat. “I don’t want to go far. Just down the river a way and back again.” A barnacle fly stung his arm, and he swatted it.

“Naw, the wheel bearings are starting to seize up too. Onliest place to get lubricant nowadays is Gireaux’s, and old Gireaux has got a bad case of the touchy-feelies. Always trying to get a little kiss or something. If I wanted to get a tub of grease out of him on short notice, I’d probably have to get down on my knees and give him a sleeve job!”

The men grinned like hounds. Pouffe, however, shook his head and sighed. “I’m going to miss all this,” he said heavily. The bureaucrat noticed for the first time the deep-interface jacks on his wrists, gray with corrosion; he’d served time on Caliban in his day. The man must have an interesting history behind him. “All your friends say they’ll keep in touch after they move to the Piedmont, but it’s just not going to happen. Who are they kidding?”

“Oh, come off it,” Aniobe scoffed. “Any man as rich as you will have friends wherever he goes. It’s not as if you needed to have a personality or nothing.”

The last timber loaded, Aniobe shut down the truck and shipped the winch. The laborers waited to be dismissed. One, a roosterish young man with a comb of stiff black hair wandered onto the porch, and casually leaned over a tray of brightly bundled feathers — fetishes, perhaps, or fishing lures. Chu watched him carefully.

He was straightening from the tray when Chu stepped forward and seized his arm.

“I saw that!” Chu spun the man around and slammed him up against the doorpost. He stared at her, face blank with shock. “What have you got in that shirt?”

“I — nothing! W-what are—” he stammered. Aniobe stood up straight, putting hands on hips. The other laborers, the bureaucrat, the shopkeeper, all froze motionless and silent, watching the confrontation.

“Take it off!” Chu barked. “Now!”

Stunned and fearful, he obeyed. He held the shirt forward in one hand to show there was nothing hidden there.

Chu ignored it. She looked slowly up and down the young man’s torso. It was lean and muscular, with a long silvery scar curving across his abdomen, and a dark cluster of curly hair on his chest. She smiled.

“Nice,” she said.

The laborers, their boss, and the shopkeeper roared with laughter. Chu’s victim reddened, lowered his head angrily, bunched his fists, and did nothing.

“You notice the way that redhead was teasing those men?” Chu remarked as they walked away. “Provocative little bitch.” Far down the street was a weary-looking building, its ridgeline sagging, half its windows boarded over with old advertising placards cut to size. The wood was dark with rot, fragmented words and images opening small portals into a brighter world: zar, a fishtail, what was either a breast or a knee, kle, and a nose pointed straight up as if its owner hoped to catch rain in the nostrils. A faded sign over the main door read terminal hotel. The torn-up remains of the railbed ran beside it. “My husband’s the same way.”

“Why did you do that to him?” the bureaucrat asked. “That worker.”

Chu didn’t pretend not to understand. “Oh, I have plans for that young man. He’s going to have a few beers now, and try to forget what happened, but of course his friends won’t let him. By the time I’ve checked into my room, sent for my baggage, and freshened up, he’ll be a little drunk. I’ll go look him up then. He sees me, and he’s going to feel a little hot and a little uncertain and a little embarrassed. He’ll look at me, and he won’t know what he feels.

“Then I’ll give him the opportunity to sort his feelings out.”

“Your method strikes me as being a little, um, uncertain. As far as effectiveness goes.”

“Trust me,” Chu said. “I’ve done this before.”

“Aha,” the bureaucrat said vaguely. Then, “Why don’t you go ahead and book us rooms, while I see about Gregorian’s mother?”

“I thought you weren’t going to interview her until morning.”

“Wasn’t I?” The bureaucrat detoured around a rotting pile of truck tires. He had very deliberately dropped that scrap of information in front of Bergier. He didn’t trust the man. He thought it all too possible that Bergier might arrange for a messenger sometime in the night to warn the mother against speaking to him.

It was part and parcel of a more serious puzzle, the question of where the false Chu had gotten his information. He’d known not only what name to give, but to leave the airship just before the real Chu boarded. More significantly, he knew that the bureaucrat hadn’t been told his liaison was a woman.

Someone in his chain of command, either within the planetary government or Technology Transfer itself, was working with Gregorian. And while it need not be Bergier, the commander was as good a suspect as any.

“I changed my mind,” he said.

3. The Dance of the Inheritors

Sunset. Bold Prospero was a pirate galleon sailing toward the night. It touched the horizon, flattening into an oval as it set continents of clouds afire. Under the trees the shadows were fading into blue air. The bureaucrat trudged down the river road, passing his briefcase from hand to hand as its weight made his palms and fingers ache.

At the edge of the village, three ragged men had built a fire in the road and were roasting yams in its coals. A dark giant sat soaking broadleaves in a bowl of water, and wrapping them about the tubers. A gray, lank man stuck them in the fire, and their aged companion raked the coals back. Two television sets were wedged in the sand, one with the sound off, and the other turned away, queasily imaging at empty trail. “Soft evening,” the bureaucrat said.

“Same to you,” the lank, colorless man said. Bony knees showed through holes in his trousers. “Have a sit-down.” He hitched slightly to the side, and the bureaucrat hunkered down beside him, resting on the balls of his feet, careful not to soil his white trousers. On the pale screen, a young man stared moodily out a window at the crashing sea. A woman stood at his back, hands on his shoulders. “Old man doesn’t believe he’s seeing a mermaid,” the lank man said.

“Well, that’s the way fathers are.” Soft blue smoke wisped into the darkening sky, smelling of driftwood and cedarbloom. “You lads out hunting?”

“In a manner of speaking,” the lank one said. The giant snorted.

“We’re scavengers,” the old man said harshly. “If that’s not good enough for you, then say so now and fuck off.” They all stared at him, unblinking.

In the sudden silence, the bureaucrat could hear the show he’d interrupted. Byron, come away from that window. There’s nothin

g out there but cold and changing Ocean. Go into the air. Your father thinks—

My father thinks of nothing but money.

“I’ve got a bottle of vacuum-distilled brandy in my briefcase.” He fetched the bottle, took a swig, held it out. “If I could convince you…”

“Well, that is hospitable.” The flask went around twice, and then Lank said, “You must be heading into the village.”

“Yes, to see Mother Gregorian. Perhaps you know her house.”

The three exchanged glances. “You won’t get anything out of her,” Lank said. “The villagers tell stories about her, you know. She’s a type.” He nodded toward the television. “Ought to be on the show.”

“Tell me about her.”

“Naw, I don’t think so.” He raised a sticklike arm, pointed. “The road dead-ends into the first street to the waterfront. Go down to the river, to the fifth—”

“Sixth,” the old man said.

“Sixth street after that. Go up by the kirk and past the boneyard to the end, right by the marshes. Can’t miss it. Big fucking castle of a place.”

“Thanks.” He stood.

They were no longer looking at him. On the screen, an albino girlchild was standing alone in the middle of a raging argument. She was an island of serene calm, her eyes vacant and autistic. “That’s Eden, she’s the boy’s sister. Hasn’t spoken since it happened,” Lank remarked.

“What happened?”

“She saw a unicorn,” the giant said.

From the air the village had looked like a very simple antique printed circuit, of the sort Galileo might have used to build his first radio telescope, if he wasn’t confusing two different eras, a comb of crooked lines leading inward from the water, too small for there to be any need of cross-streets. The houses were small and shabby, but warm light spilled from the windows, and voices murmured within. An occasional dog stridently warned him away from boat or yard. Other than an innkeeper who nodded lazily from the door of the watermen’s hotel, he met no one by the riverfront. He turned onto the marsh road, the river cold and silver at his back. He went past a walled-in ground where skeletons hung from the trees, the bones bleached and painted and wired together so that they clacked gently in an almost unnoticeable breeze.

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

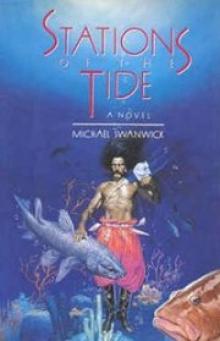

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors