- Home

- Michael Swanwick

Vacuum Flowers Page 6

Vacuum Flowers Read online

Page 6

The court was full of people looking for an exit that was not there. For every one who realized that and left, two more came in. They pushed and shoved at each other, and even exchanged blows in their blind flight.

Then the gateway filled with jackboots. They were a motley bunch, in all color of cloak and even work garb. One woman wore a welder’s apron, though she seemed to have lost her mask. All had red stripes down the center of their faces, and fierce, merciless expressions. Three of them grabbed a young boy and fit a programmer across his forehead. He thrashed and then went passive. A fourth held a piece of paper to his face, and he shook his head. He was shoved out the gateway, and another civilian was seized.

One of the processers was called away, and the next civilian questioned was programmed police. Somebody repainted her face, and someone else shoved a fistful of papers at her. One went flying, and Rebel saw that it was a cheap repro hologram. Her face—her new face, Eucrasia’s face—floated above the paper, twisting and folding into itself when the paper doubled up against a hut.

Rebel shivered and tried to keep from thinking about it. Later.

A heavy, bullish man snapped a length of pipe from a doorframe and tried to smash his way through the gate. One jackboot fell back, clutching his head, but others seized the man’s arms and legs and forced a programmer to his brow. “You’re a strong one,” the welder laughed as the samurai look came on his face. She drew a red stripe from his chin to his hairline. He joined the line.

Rebel’s leg itched furiously. She did not move a muscle.

As the people were processed out and the courtyard emptied, those who remained grew calmer. Some even formed a sullen line, to get through the questioning more quickly.

There was a flurry of conferences, and four new jackboots entered. Three of them were permanent police, felons who’d pulled long enough terms to merit extensive training. They wore riot helmets with transparent visors, and low-mass body armor. Their insignia identified them as corporate mercenaries, rather than civil police. Two carried long staffs with conplicated blades at their ends, like a cross between a pike and a brush hook.

The fourth was Maxwell.

There was no doubting it. The four passed right by Rebel’s hiding place, and she got a good look at the young man. He had a stripe of killer red up the center of his face and a glittery, unforgiving look to his eye. “Of course I’m not mistaken,” he snapped. “I heard her story myself. It’s Deutsche Nakasone that’s sponsoring this raid, right? Well, that’s who she escaped from. How could I be mistaken?”

He led the others to his hut and watched complacently as they ripped the front wall off, sending his jewelry and clothes scattering through the court. Moving efficiently, they jammed their hooks into the rear wall and began cutting it free of the frame.

Rebel had a horrible urge to sneeze. She wanted to scream, to break and run. But that was Eucrasia’s impulse, and Rebel would not give in to it. The jackboots at the gateway were processing out the last three tank towners. Their motions were quick and alert.

The thing to do was not to move.

I am old sister pike, she thought to herself. I am patience.

The rear wall went flying, and the police jabbed their poles into the vines behind it. Maxwell shouted a warning, and they ignored it. He waved his arms frantically.

And men there were cries of dismay. With an angry shrill, a swarm of honeybees rose from their broken hive.

The police fell back, swatting and cursing. At the gateway, somebody grabbed a jerrycan of water from Jonamon’s hut and flung its contents at the swarm. The water broke into spheres and smashed into both bees and jackboots, doing nothing for the temper of either. The permanent jackboots retreated to the corridor, dragging Maxwell after them. One cursed him furiously.

Maxwell answered back and was struck in the mouth.

The courtyard emptied. The jackboots pulled away from the gateway, and soon only one lingered. Go away, Rebel thought at him. But he did not. He gazed long and thoughtfully at the floating debris in the courtyard and the occasional bee zipping angrily by. He kicked into the court and poked his head into a hut or two.

The man examined a vine-filled gap halfway across the court from her. Then he swam over to her patch. Rebel closed her eyes so the reflection from them would not betray her. Her skin itched.

The vines rustled slightly. “Heads up, Sunshine!”

She opened her eyes.

It was Wyeth, painted as if programmed police. Those fierce eyes laughed at her from either side of the red stripe, and he grinned comically. Then his face went grim again, and he said, “We’ll have to get a move on. They’re going to be back.”

She climbed out of the vines. Following Wyeth’s lead, she recovered her helmet and vacuum suit. Wyeth was at the gate, calling to her to hurry, when she noticed something floating half-hidden by a sheet of tin in an obscure corner of the court. “Wait,” she said. It was a body.

Rebel kicked away the tin. Old Jonamon floated there, pale and motionless, like a piece of detritus. At her touch, he opened one eye. “Careful now,” he muttered.

“Jonamon, what did they do to you?”

“I’ve survived worse. You think maybe you could get me some water?” Wyeth silently fetched a bulb and held it to the old man’s mouth. Jonamon sucked in a mouthful and coughed it out, choking. When he’d recovered, he gasped, “It’s hell being old. Don’t let nobody tell you different.”

The old man was all tangled up in his cloak. Gently, Rebel unwrapped it. When she saw his body, she gasped. “They beat you!”

“Ain’t the first time.” Jonamon tried to laugh. “But they couldn’t put their programmer on me without they beat me unconscious first.” His arms moved feebly, like a baby’s. “So I escaped.”

Rebel wanted to cry. “Oh, Jonamon. What good did that do you? You might have been killed!”

Jonamon grinned, and for a second Rebel could see the young, avaricious man of the old hologram. “At least I’d’ve died in a state of grace.”

Wyeth drew Rebel away. “Sunshine, we don’t have much time.”

“I’m not leaving without Jonamon.”

“Hmm.” He cracked his knuckles thoughtfully, and his lips moved in silent argument with himself. “Okay, then,” he said finally. “You fake the one arm and I’ll take the other.”

They moved slowly downcorridor, the old man between them. His mouth was open and his eyes half shut with pain. He didn’t try to talk. The tank towners, seeing Wyeth’s jackboot paint, gave them a wide berth. “Queen Roslyn has her court down this way,” Wyeth said. “She’s a predatory old hag, and she stocks a lot of wetware. If anybody has a hospital going, it’ll be her.”

They followed a purple rope into a dark neighborhood with one brightly lit gateway. People hurried in and out of it. Rebel didn’t need to be told that this was their destination.

At the gateway, an angular woman with bony shoulders and small, black nipples blocked their way. “Full up! Full up!” she cried. “No room here, go someplace else.” She didn’t even glance at Jonamon, who was now fully unconscious.

Wordlessly, Wyeth stripped the salaries from one wrist and held them forward. The woman cocked an eye at them, then let her gaze travel to his other wrist. Wyeth frowned. “Don’t get greedy, Roslyn.”

“Well,” Roslyn said. “I guess we could make an exception.” She made the salaries disappear, and led them inside.

It was chaos in the court, with stretcher lines hung up every which way. The lines were crowded with wounded rude boys and rude girls, temporary jackboots, unpainted religious fanatics, and even one tightly bound raver. A miasma of blood droplets, trash, and bits of bandages hung in the air. But people with medical paint moved among the wounded, and their programming seemed efficient enough. Roslyn stopped one and said, “Give this guy top priority, okay? His friends are paying for it.” The tech gave a tight little nod and eased Jonamon away. Roslyn smiled. “You see? Ask anyone, Roslyn gives good v

alue. But you got to go now. I got no room for bystanders.” She shooed them back.

On the way out, Rebel suddenly spotted a familiar face. She seized Wyeth’s arm and pointed. “Look! Isn’t that …?” Maxwell was stretched out on a line, unconscious. The red police strip was smudged on his finely chiseled face.

Roslyn saw the gesture and laughed. “Another friend of yours? You oughta maybe get some new ones who can stay out of trouble. But he’s okay. Might lose a tooth. But mostly he’s just got a histamine reaction from being bee-stung too often.” They were at the gateway now. “Young woman brought him in. Pretty little thing.” She cackled. “I think she’s sweet on him.”

“Oh?” Rebel said coolly. “Well, it takes all kinds, I guess.”

They moved through near-empty corridors, away from the center of the tank, and away from the receding storm front. “Wyeth,” Rebel said after a long silence, “Jonamon’s problems are all the result of his calcium depletion, aren’t they?”

“Jonamon’s problems are all the result of his being a stubborn old man. He’ll survive this time, but it’s going to kill him sooner or later.”

“No, really,” Rebel insisted. “I mean, like the kidney troubles, he gets them from the calcium depletion right? You watch him for any length of time, and you see that he gets muscle cramps, his breathing gets irregular.… So why hasn’t he had that corrected?”

They were nearing the shell. The temperature was cooler here, up against the outside of the tank. Wyeth paused, took a narrow sideway, and Rebel followed. “It’s not correctable. You live a year or so in weightlessness, and you reach the point of no return. It can’t be reversed. Slow down, we make a turn soon.”

“But it would be so simple. You could tailor a strain of coraliferous algae to live in the bloodstream. In the first phase they’re free-swimming, and in the second they colonize the bone tissue. When they die, they leave behind a tiny bit of calcium.”

“Coral reefs in the bones?” Wyeth sounded bemused.

“That’s how we do it back home.”

“You come from an interesting culture, Sunshine,” Wyeth said. “You’ll have to tell me all about it someday. But right now … here we are.” The corridor they had entered was completely shuttered and lit only by nightblooms. Scattered trash gathered in long drifts unbroken by the passage of traffic. They were the only people in sight. Silently, Wyeth moved down the corridor, looking for a particular door. When he found it, he stopped and rattled a wall. “This is King Wismon’s court. He’s got something we need.”

“What’s that?”

“A bootleg airlock.”

4

LONDONGRAD

“You’re too late. I’m afraid. You’ll simply have to go away.”

Eyes closed, King Wismon floated in the center of his court. In stark contrast to the skinny young rude boys who had ushered Rebel and Wyeth through twisty passages to the court and who now stood guard over them, Wismon was enormously fat. His was the kind of fat that is only possible in a zero-gee environment. Even in half gravity the weight of his bloated flesh would have strained his heart, pulled his internal organs out of place, stressed muscle and bone, and threatened to collapse his lungs. His arms were unable to touch around the vast curve of his stomach, and his skin was mottled with patches of blotchy red. His crotch was buried under doughlike billows of leg and belly, rendering him an enormous, sexless sphere of flesh.

“We have to be gone before the police front comes by again!” Rebel held forward her wrists. “We can pay!”

Without opening his eyes, Wismon said, “I have been paid for use of my airlock five times today. That is enough. The lock is the basis of whatever small affluence I have—I don’t want to draw attention to it. The secret of a good scam is not to get greedy.”

“Hallo, Wismon,” Wyeth said. “No time for an old friend?”

The fat man’s eyes popped open. They were bright and glittery and dark. “Ah! Mentor! Forgive me for not recognizing you—I was asleep.” He waved an ineffectual little arm at the rude boys. “Leave. This man is a brother under the skull. He won’t harm me.”

The rude boys backed away, suspicious but obedient. They disappeared.

For an instant Eucrasia’s technical skills came back to Rebel, and in a flash of insight she read the eyes, the facial muscles, that weird, smirking grin.… This was not a human being. This was a mind that had been reshaped and restructured. The play of intelligence behind those dark eyes was too fast, too intuitive, too perceptive to be human. Its mental life would be a perpetual avalanche of perception and deduction that would crush a normal human persona.

Rebel realized all this in an instant, and in that same instant saw that Wismon had been studying her. Slowly, solemnly, he winked one eye. To Wyeth, he said, “For you, mentor, I’ll gladly violate my own protocol. Go ahead, use the lock, I won’t even charge you for it. Just leave me the woman.”

Rebel stiffened.

“I doubt she’d be of any use to you,” Wyeth said. His eyes were flat and intent, a killer’s eyes—there was no impatience in them at all. “But even if she were, Deutsche Nakasone is after her. Do you really feel like going up against them? Eh?”

There was a dark explosion of hatred in those little eyes. “Perhaps I do.” Wismon smiled gently.

“Now wait a minute, don’t I have any say—” Rebel and Wismon said in unison. Rebel stopped. She stared at Wismon in mingled outrage and amazement.

“Don’t interrupt, little sweets,” Wismon said in a kindly voice. “I can read you like a book.” He peered owlishly at Wyeth.

With a slight edge in his voice, Wyeth said, “Let’s put it this way. Do you feel like going up against me?”

A long silence. Then, “No, damn it.” One of Wismon’s little hands reached up to scratch convulsively at the side of his neck. It left red nail tracks. Then Wismon grinned companionably and said, “You’re bluffing, mentor, but I don’t know about what. I never was able to read you. Go through the hutch to your left—the one with a green rag for a door. You’d oblige me by both leaving at the same time. It’s a tight squeeze, but I’m sure you’ll manage.”

They kicked out of the airlock arm in arm. Rebel touched helmet with Wyeth. “What was that all about?”

“An old friend.”

They drifted slowly toward the butt end of the Londongrad cannister. It was a great dark circle that did not seem to grow any closer. A tangle of bright machines flashed by. Behind them, the tank towns slowly shrank. “He was afraid of you.”

“Well … I did most of his reprogramming. When you put together a new mind, it’s kind of traditional for the programmer to put a Frankenstein kink in the program, just in case. Sort of a dead man’s switch. So that with a prearranged signal—a word, a gesture, almost anything—the programmer can destroy the personality.”

“I see.” It all had a familiar ring; this was something Eucrasia had understood well. “Was that what you did?”

“Of course not. That would be immoral.” They floated through unchanging vacuum for a time. Then Wyeth said, “He’d only have found it and canceled it out, anyway. This way I can keep him guessing.”

Helmets touching, his face was intimately close. It filled her vision, craggy and enigmatic. Those green eyes of his sparkled. “How can you be sure he’d’ve found it?”

“Why not? He’s smarter than I am. And I found the kink you put in me.” He pulled his helmet away, and silence wrapped itself around her.

The cannister approached with extreme slowness. Rebel felt a queasiness that was like a snake uncoiling in her stomach and slithering up her spine. It curled around her head twice and constricted slightly. Eucrasia’s claustrophobia. She swallowed hard. I won’t give in to it, she thought. It can’t break me. It can only make me stronger.

It was not an easy trip.

Not many hours later they were following a pierrot into one of Londongrad’s most exclusive business parks. Under the canopy of druid trees, languid paths

lit by wrought-iron lampposts meandered through dark fields and small stands of trees. Fireflies drifted hypnotically through the grass. A snowy owl swooped down on them, snapped out magnificent white wings at the last possible instant, banked, and was gone. “Wyeth,” Rebel asked, “why did we spend all your money on these clothes? There were cloaks that looked just as good for nowhere near as much.”

“Yes, but they weren’t made of real Terran wool. When you go to the rich to ask for money, you must never let them suspect you actually need it.”

“Oh.”

“Now don’t talk. Remember you’re painted up as a recreational slave. So don’t smile, don’t talk, don’t show any initiative. Just tag along.”

Rebel moved her crossed wrists back and forth, setting the leash connecting them to Wyeth’s hand swinging. “Yeah, well, I’m not exactly thrilled about this part of the deal either.”

“It gives you an excuse for following me around. More importantly, it’ll confirm all of Ginneh’s worst suspicions about me. She’ll love it.” He hesitated, looked embarrassed. “Look, if it’d be any easier on you, I could take a minute and program you up for real. It’s only for an hour or so, anyway—”

“No goddamn way!” she said, and Wyeth nodded quickly and glanced away. Rebel’s revulsion went right down to the bone, so complete she was certain it came from both of her personas. Well, that was one thing she had in common with Eucrasia.

The pierrot halted and, bowing, gestured to one side with a white-gloved hand. A brick walk led around a lilac bush to a simple office—a floating slab of polished wood for a desk, and two plain chairs—backed by a rock outcrop and sheltered by a Japanese maple. At their approach a small, quick woman rose. “Wyeth, dear! It’s been years since I’ve seen you.” Her skin was somewhere between amber and mahogany, her eyes midway between shrewd and cunning. She dressed corporate grey, down to the beads of her braids, and her nails were scarlet daggers. Her business paint brought up her cheekbones, played down her wide mouth. She gave Wyeth a swift hug and a peck on the cheek.

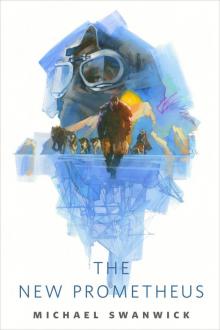

The New Prometheus

The New Prometheus The Iron Dragon’s Mother

The Iron Dragon’s Mother The Mongolian Wizard Stories

The Mongolian Wizard Stories The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus

The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus Day of the Kraken

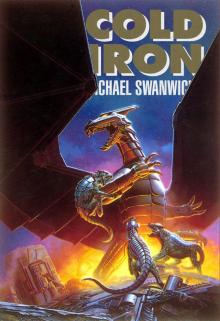

Day of the Kraken Cold Iron

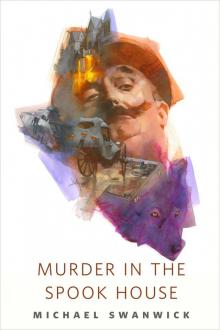

Cold Iron Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original

Murder in the Spook House: A Tor.com Original Radio Waves

Radio Waves The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original

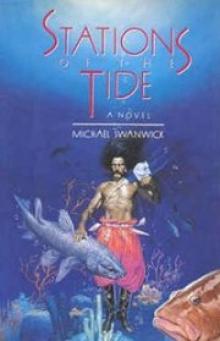

The New Prometheus: A Tor.com Original Stations of the Tide

Stations of the Tide Vacuum Flowers

Vacuum Flowers The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7)

The Mongolian Wizard Stories (online stories 1-7) The Dragons of Babel

The Dragons of Babel The Dog Said Bow-Wow

The Dog Said Bow-Wow Griffin's Egg

Griffin's Egg The Best of Michael Swanwick

The Best of Michael Swanwick Not So Much, Said the Cat

Not So Much, Said the Cat In the Drift

In the Drift Vacumn Flowers

Vacumn Flowers Slow Life

Slow Life The Wisdom Of Old Earth

The Wisdom Of Old Earth Legions In Time

Legions In Time Scherzo with Tyrannosaur

Scherzo with Tyrannosaur The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition)

The Year's Best Science Fiction (2008 Edition) The Iron Dragon's Daughter

The Iron Dragon's Daughter The Very Pulse of the Machine

The Very Pulse of the Machine Zeppelin City

Zeppelin City Dancing with Bears

Dancing with Bears Bones of the Earth

Bones of the Earth Tales of Old Earth

Tales of Old Earth Trojan Horse

Trojan Horse Radiant Doors

Radiant Doors